Part I — The Emergence of the Princes

- India at the End of the Eighteenth Century

- The Marathas

- Decline of Maratha Power

- Lord Wellesley and the Peshwa

- British and Maratha Diplomacy

- The Death of Nana Farnavis

- The Battle of Poona

- The Treaty of Bassein

- Collins and Metcalfe at Poona

- Outbreak of the Second Anglo-Maratha War

- British and Maratha Military Tactics

- Lake Opens His Campaign

- The Battle of Delhi and the Fall of Agra

- The Battle of Laswari

- General Wellesley’s Victories

- The Making of the Treaties

- Difficulties Following the Conclusion of Peace

- Yeswant Rao Holkar

- First Stages of the War with Holkar

- The Siege of Bharatpur

- Bharatpur and Indian and British Reactions

- Arrival of Lord Cornwallis

- Considerations of the Peace

- The War’s Results

- The Psychological Change in the Conquerors

Part II — British Paramountcy

- Mutinies. The Chaos of Central India

- The Company’s Embassies

- Domestic Troubles and Colonial Expeditions

- The Mogul Emperor and Delhi

- Metcalfe and Central India

- The Company’s Satraps

- The Gurkha War

- The Peshwa and Gangadhar Sastri’s Murder

- The Pindaris and the Chaos of Central India

- Preliminaries of the Pindari Campaign

- Elphinstone and the Peshwa

- Amir Khan. The Rajput States

- The Peshwa’s Outbreak

- The Nagpur Outbreak

- The Campaign against Holkar

- Surrender of the Peshwa

- The British Leaders and the Common Soldier

- Reflections: Political

- Status of the Princes. The King of Delhi

- The Doctrine of Paramountcy

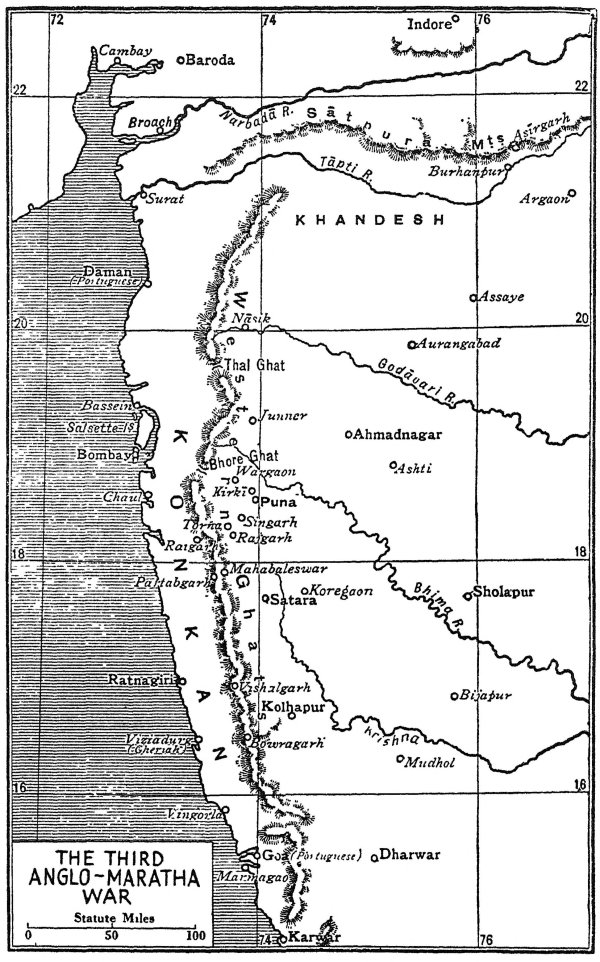

Maps

Preface

Now that India’s right to independence has been acknowledged, the Princes’ rights and status remain her outstanding constitutional problem. It cannot be decided by mere legal examination of their treaties with the Paramount Power. There exists, in addition. a body of practice and tradition. Also, there arises the question of the status and position of the parties to those treaties when they were made. This question only a knowledge of the events which shaped India’s political framework can answer.

India’s political framework was made in twenty years: in 1799-1819, between the death of Tipu Sultan and the elimination of the Peshwa. The period opens with the destruction of the Muslim kingdom of Mysore and ends with the disintegration of the Maratha Confederacy into a series of separate chieftaincies. These two conquests gave the British the control of India.

After Tipu’s destruction the Marathas remained. When they were finally beaten down, Modern India was formed and its map in essentials drawn. The arrangement was to stay until the slow process of time and the coming of new systems of political thinking made it an anachronism, calling for Round Table Conferences, White Papers, and their sequel in constitutional legislation and political offers. India, as we knew it yesterday and the world has known it, was made in the space of these twenty years, first by the shattering of what Lord Wellesley styled ‘the Mahratta Empire’ and then, after a brief period of uncertain and faltering doctrine, by Lord Hastings’ firm establishment of the States which had survived, each in the niche and status which was to be legally accepted as its own until our day. The Indian ‘Prince’ emerged in 1806, arising, like the Puranic Urvasi,[^1] from the churning of the Ocean by the Gods and Demons, and received his position in India’s polity in 1819.

In these twenty years were three major wars, the last major wars to be fought in India, except for the two Sikh wars, and one minor campaign. A detailed study of the first of these, that between the British and Tipu Sultan, lies outside my present purpose. The Muslim dynasty of Mysore was an excrescence, whose roots lay in the personal qualities of two unusually vigorous alien rulers. It never challenged the overlordship of all India.

It was the second of these wars, the Second Anglo-Maratha War, that revealed the outlines of the India which was ultimately to escape absorption into the British system. Its result involved the subordination of ‘the country powers’ to the East India Company’s Government, whose paramountcy now merely waited for the name. After 1819, only stupidity or hypocrisy or an excess of tactfulness could pretend that the East India Company was not the Paramount Power or that any of the Princes were its equals in status; the Third Anglo-Maratha War had made this clear.

Indeed, the rebound to an opposite opinion was so extreme that for close on forty years it seemed doubtful if the Princes would survive at all. The Paramount Power made no secret of its intention to annex their territories whenever a pretext could be found. The Mutiny caused a sharp revision of this attitude, and when it ended the Princes were ceremoniously re-established where 1819 had left them. The historian therefore finds himself compelled continually to return to twenty all-important years, to explain all the years which have followed.

‘Personality’ history is not now in vogue. A historian whose approach is through the medium of men rather than economic factors and trends is suspected of leanings to the Ruritanian school of history, a pleasant region halfway between history proper and the historical novel. The modern reader may therefore be deterred when he glances through these pages, to see an apparently multitudinous field of princes and princelings, chieftains and satraps and functionaries in the various secretariats. Historians of Modern India have been oppressed by the mass of detail unfamiliar to their readers, which they must handle and build into generalizations, and have not unnaturally been preoccupied with Governors-General and Commanders-in-Chief. In particular, Native India and its leaders have made only incidental appearances, their motives rarely understood or even regarded, their personalities left shadowy. Our writing of India’s history is perhaps resented more than anything else we have done.

It has also resulted in error and misconception on our side. For us, over a century later, to accept the Princes as they are presented after that century—during which they have been a part of India yet separated from British India and in nearly all that concerned India as a whole almost passive agents—and to assume a modern attitude of over-simplification to a polity and constitution which were worked out by a succession of hammer-blows alternating with much wise and patient action, is to misunderstand India entirely. There is no other road to understanding the Princes and the problem their position and status now are, than by going through twenty significant years in detail, weighing the imponderables of personal forces as the men of that time had to weigh them.

To obtain this knowledge, one must have access to the diaries, minutes, reports, and records of the time, of which many have never yet been used. This brings me to the duty of acknowledgment of help that can rarely have been given so generously and by so many. Ten years ago, the Leverhulme Trustees by the award of a research fellowship enabled me to begin a study which was to take me far afield, into small dark rooms in remote places, where I found myself turning over bundles of mouldering letters of once-powerful men long dead, records tied up in roomals (handkerchiefs) and often still unsorted. The representatives of Lord Metcalfe put into my hands practically all that survived of his correspondence; for this kindness I am indebted to Miss Clive Bayley above all, and for much additional information. The India Office, and Dr. H. N. Randle, its librarian, gave free access to their own records. Lord Lothian, Secretary of the Rhodes Trust, cared about India and cared about history, and the Trustees twice gave me a grant to visit India in search of material. Friends like Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru told me historical details which they came across in law practice, some of them throwing light on men before my period, such as Warren Hastings. M. R. Jayakar put me in touch with men who held the key to Maratha traditions and manuscripts. Sir Akbar Hydari gave me the freedom of the Hyderabad records. Jawaharlal Nehru drew my attention to matters which an Englishman, left to himself, would be bound to overlook. Rai Saheb Sardesai left his remote home in the Western Ghats, to help me as no other student of Maratha history could. Lieutenant-Colonel Reginald Schomberg, D.S.O., C.I.E., my friend from days when we were both before Kut, introduced me to the Records Department of the Bibliothèque Nationale, Pondichéry. I have been allowed to examine records in Persian, Marathi, French, Urdu, Bengali, as well as my own tongue.

I wrote first my Life of Lord Metcalfe, I had known in a general way how remarkable and noble a man he was. But I had known far less than the reality, and I saw that I must go yet further and try to light up a whole period, a whole vanished and scarcely realized generation. The period 1799-1819 has not merely a political importance. It has a personal interest exceeding that of any other period in British-Indian relations.

No other period threw up so many men who were outstanding in gifts and character. Our nation has not begun to be aware of even their intellectual quality. Such a letter, for example, as the one Elphinstone (whose letters I have seen lying in scores, still awaiting study) wrote immediately after the Battle of Assaye should be famous. It came from the brain swiftly and was sent as it came, but no professional writer who ever lived could better it as literature in a single phrase. And Elphinstone habitually wrote on this level or very near it. Nor is there much wrong with the letters, written without any thought of their being ‘literature’, of Metcalfe and Malcolm (except that their handwriting is a sorrow to read, and Malcolm’s in particular, especially in his later days, something which ought to be an offence against the law). They were wonderfully attractive men, vivid and eager and in the main tolerant and far-seeing. They have hardly had their equals in British history of any land or age.

Part of the reason for this intellectual quality was their experience. It was in this period, and most of all in the earlier of its two Maratha campaigns, that the British became ‘acclimatized’ in India. The psychological change and shift in their attitude was immense. Before this, their people had been adventurers. Now they were in India to stay. This compelled a revolution in thought, and not least in its subconscious levels.

Men to whom a change like this comes rarely themselves perceive it. But the historian has no right to look through his material so carelessly as to miss it. Perception of this change came to me, not in official despatches, but in the hurried and often confused letters of quite unimportant men, who had done little serious thinking in their lives but found themselves in the presence of a new world that forced thinking upon them. I have tried to make these men, and their leaders especially, living and distinct, and make no apology for citing freely incidents which might be regarded as trivial and beneath the dignity of history. In the process I learnt also how vivid and attractive were many of those Indian leaders who before had been little more than mere names of men who had gone down in defeat and hopeless resistance.

In conclusion, I return to acknowledgment of indebtedness. Most of all, I am in the debt of Mr. and Mrs. H. N. Spalding, who established a fellowship in Indian historical research, and to the Provost and Fellows of Oriel College, who accepted it and elected me to their number. Their steady kindness and interest can never be adequately acknowledged. I owe thanks, for facilities or advice, to the Rev. E. W. Thompson, M.A., who looked through a very early draft of this book: Mr. Dinkar Ganesh Bhide and Mr. Narayan Shivram Nadkarni, of the Bombay Records Office: Mr. D. B. Diskalkar and Mr. Bhusani, of the Parasnis Museum, Satara: the Officers of the Hyderabad State Records: Mr. H. G. Rawlinson, C.I.E.: Dr. T. G. P. Spear: Sir Patrick Cadell: and Sir William Foster, C.I.E.: the late Philip Morrell.

E. T.

Oriel College,

Oxford.

20 January 1943.

Part I — The Emergence of the Princes

I

India at the End of the Eighteenth Century

The Marattahs possess, alone of all the people of Hindostan and Decan, a principle of national attachment, which is strongly impressed on the minds of all individuals of the nation, and would probably unite their chiefs, as in one common cause, if any great danger were to threaten the general state.

— Warren Hastings, in 1784India contains no more than two great powers, British and Mahratta, and every other state acknowledges the influence of one or the other. Every inch that we recede will be occupied by them.

— Charles Metcalfe, in 1806.

Warren Hastings left India in 1784. On his voyage home he drew up an analysis of its political condition.[^2]

The list of Powers which might be considered independent had shrunk from one cause or another, the East India Company having been the most effective dissolvent: ‘it seems to have been the fixed policy of our nation in India to enfeeble every power in connection with it’. The Mogul Emperor, though hardly worthy to be reckoned among Powers of any sort or kind, he mentions because of the prestige attaching to his ancestors and in some degree to his person. The Nawabs of Oudh and the Carnatic, nominally servants of the Emperor, he notes as entirely dependent on the Company. Another nominal officer of the Emperor, the Nizam of Hyderabad, he sees in the position of a star destined to become a satellite but now the object of contention between rival heavenly bodies:

‘His dominions are of small extent and scanty revenue; his military strength is represented to be most contemptible; nor was he at any period of his life distinguished for personal courage or the spirit of enterprise. On the contrary, it seems to have been his constant and ruling maxim to foment the incentives of war among his neighbours, to profit by their weakness and embarrassments, but to avoid being a party himself in any of their contests, and to submit even to humiliating sacrifices rather than subject himself to the chances of war.’[^3]

There were also a number of small principalities, whose safety was in lying quietly under the shadow of some greater Power. Some of these, notably the Rajput states, all nominally dependents of the Emperor though actually fallen within the orbit of the Maratha chieftain Sindhia, were respectable from their antiquity.

They still survive, almost the only States with a title older than that of the British Government or with one not originally derived from an office under the Mogul Emperor.

The Punjab was unsettled. The Sikhs (as Hastings notes, a sect rather than a nation) were there struggling with Mussulman invaders and adventurers. Apart from this and other districts beyond the Company’s present purview—such as Nepal, Sind, and Kutch—in India Hastings saw only two genuinely independent Powers, Tipu Sultan in the Mysore, and the Maratha Confederacy straddling across Central India and now reaching far into the north, controlling Delhi itself. It was certain that sooner or later war would come between these two Powers and the British.[^4]

The Destruction of Tipu Sultan

The first of the wars which Hastings foresaw began when Tipu (29 December 1789) attacked the Company’s ally, the Raja of Travancore. ‘That mad barbarian Tippoo has forced us into a war with him.’[^5] It ended, 1792, in Tipu’s utter defeat. But the peace which followed this Third Mysore War was to be merely an armistice.

In the decade that ended the century, Tipu was in fitful communication with the French. Raging from his loss of a huge indemnity and of half his dominions, he felt blindly for allies, inside and outside India. This restlessness in no way differed from the normal behaviour, then or since, of warring or threatened States, but it was reprobated as proof of his ingrained faithlessness. His quarrel with the British was one of deep mutual hatred; the stories of his treatment of captives had rung through England.

Three wars only—the two World Wars and that against Napoleon—have been waged by the British with a conviction that defeat meant submergence. During the Napoleonic War the ruling oligarchy knew that the commerce which brought it wealth and financed the political arrangement which secured enjoyment of that wealth was threatened. When the Earl of Mornington reached India as Governor-General, May 1798, his class had worked itself into a frenzy of patriotism and exasperation against Jacobinism (a term used as widely and loosely as such terms as ‘Red’, ‘Left’, and ‘Communism’ in recent years) and against Buonaparte. The latter was entangled in his Egyptian and Syrian adventure, which in retrospect appears a mere escapade but at the time was accepted as a serious attempt to break through to the growing British Empire in the East. Such a break-through was, as a matter of fact, part of Napoleon’s larger hope. The new Governor-General came resolute to end the Company’s quarrel with Mysore once for all. He regarded this as his contribution to Buonaparte’s defeat.

Madras, long sunk in selfishness and corruption, and Bombay, an isolated and fragmentary property overshadowed by the power of the Marathas, he found hard to stir. But he infused his own excitement and enthusiasm into the British of Bengal. Calcutta subscribed and sent home, July 1798, £130,785 3s. 1½d., a sum which included a small contribution by Indians.[^6] There was immense, if passing, zeal to enrol as volunteers against invasion by the Corsican ogre, and plans were drawn up for the defence of the capital. Gentlemen turned out on Calcutta maidan,[^7] complete with sidearms and musket, and attended by native servants carrying umbrellas, and bricks to put beneath Master’s feet if Master had to drill in squashy places. The season was the monsoon, when the maidan, even now, can be very wet.

Tipu could hardly have escaped destruction by even the most circumspect humility. He gave a casus belli by inept negotiations with the French Governor of Mauritius,[^8] which the latter boastfully published. These intrigues, with a not very important official, furnished an excuse for the war which Lord Mornington would have made in any case. It began in February 1799, and was over in three months. Seringapatam was stormed (May 4), and the Sultan’s body was found in a pile of about five hundred crowded into a small space. The Governor-General’s brother, Arthur Wellesley, as unshakably phlegmatic as Lord Mornington was excitable, standing in torchlight felt heart and pulse, and reported Tipu to be lifeless. His conquerors buried him with military honours, in which the elements joined, sweeping the island with a tempest of thunder and rain such as was hardly remembered in even that storm-ravaged region.[^9]

A shrunken Mysore was placed under a Prince of the Hindu dynasty which Tipu’s father, Haidar, had dislodged. The new Maharaja, a child,[^10] showed a ‘highly proper’ decorum during the ceremony of his enthronement. His family, who had been discovered in abject poverty, behaved equally well, and acknowledged their grateful sense of dependence. ‘We shall at all times’, the two ladies of highest distinction told the Commissioners for the settlement, ‘consider ourselves as under your protection and orders... . Our offspring can never forget an attachment to your government, on whose support we shall depend.’ This language was rather more than the flowery recognition of favours received, which etiquette and custom prescribed. It underlined what was obvious; Mysore had become a puppet state. Its pacification was undertaken by a group of able soldiers, who afterwards left administration in the hands of Purnayya, a veteran Brahman politician, who governed it as Dewan.[^11]

The French, all but ejected from India, had long watched despairingly from Pondichery, conscious of their inability to help a state which they had encouraged into wars which destroyed it. To Cornwallis’ campaign against Tipu, ten years earlier, they had given close and unremitting attention, and at its close exclaimed that at last both Nizam and Marathas must surely have their eyes opened, and begin to see how unwise they had been in warring against Mysore, thereby enfeebling the only Power ‘qui puisse en imposer aux anglais’.[^12]

Haidar and Tipu brought the East India Company nearer to ruin than any other Indian foes had brought it, and nearer than any subsequent foe was to bring it. But they were an episode only, lasting less than forty years. They took no root among the country powers.[^13] With the Marathas, the greatest of these powers, Tipu’s destruction left the Company fairly face to face.

II

The Marathas

The Marathas are a hardy nation from the Deccan and Western Ghats. Their homeland, Maharastra, lies between the 16th and 22nd degrees of north latitude, and stretches from the Satpura Hills to the Wainganga[^14] and Wardha rivers, and to the borders of Goanese territory.

They became prominent in the later decades of the seventeenth century, under Shahji and his celebrated son Sivaji. The Rajputs had hitherto been the spearhead of Hindu resistance to the Mogul Empire. They now weakened, worn down by long and desperate fighting, and the Marathas took their place. Sivaji, founder of Maratha greatness, was a particularly devout Hindu and fought for Hinduism almost as much as for his own hand. For this reason, and because the Marathas were peasants, low in the caste scale, their Brahmans had exceptional power and influence. One main cause of the ascendancy which the Peshwas obtained was the fact that they were Brahmans and their persons sacred, whatever their misdeeds. This essential consideration is often overlooked.

With our recent historians, the Marathas’ reputation is that of robbers pure and simple. It is true that this opinion can find support in the great authority of Sir Thomas Munro. ‘The Mahratta Government, from its foundation, has been one of the most destructive that ever existed in India.’[^15] But Munro’s service was in Mysore and Madras, and he saw the Marathas solely as enemies; he never was where he could understand Northern India, an entirely different world from the South, and one which all through the centuries has had a different history and outlook. His exasperated witness was written in 1817, when for many years the Marathas had been the dregs of what they were. Munro himself was then marching against their last Peshwa, a man in whom no one has yet found any good quality, his memory still felt as a humiliation to the nation that he ruined.

Most of the distinguished men who dealt directly with the Marathas thought better of them. Hindu India cherishes their memory with pride, and they could not have conducted their protracted and successful fight against the Mogul Empire, without the support of the regions by whose resources they subsisted. We cannot

‘deny to the Mahrattas, in the early part of their history, and before their extensive conquests had made their vast and mixed armies cease to be national, the merit of conducting their Cossack inroads into other countries with a consideration to the inhabitants, which had been deemed incompatible with that terrible and destructive species of war.’[^16]

An officer who knew them exceptionally well, though he bears testimony to the desolation that they brought—‘a Mahratta army are more indefatigable and destructive than myriads of locusts’—and speaks of the hardness of heart acquired from warfare,[^17] which as in the case of Prussia had become their ‘national industry’, gives us also this attractive picture of their ‘great simplicity of manners’:

‘Homer mentions princesses going in person to the fountains to wash their household linen. I can affirm having seen the daughter of a prince (able to bring an army into the field much larger than the whole Greek confederacy) making bread with her own hands, and otherwise employed in the ordinary business of domestic housewifery. I have seen one of the most powerful chiefs of the empire, after a day of action, assist in kindling a fire to keep himself warm during the night, and sitting on the ground on a spread saddle-cloth, dictating to his secretaries and otherwise discharging the political duties of his station. This primeval plainness operates upon the whole people. There is no distinction of sentiment to be discerned: the prince and his domestics think exactly in the same way, and express themselves in the same terms. There appears but one level of character, without any mixture of ardour or enthusiasm; a circumstance the more surprising, considering the great exploits they have achieved. But their simplicity of manners, uncorrupted by success, their courtesy to strangers, their unaffected politeness and easiness of access, must render them dear to every person that has had a commerce with them. Such a character, when contrasted with the insidiousness of the Brahman, and the haughtiness of the Mussulman, rises as superior to them, as candour and plainness are to duplicity and deceit, or real greatness to barbarous ostentation.’[^18]

India, usually under the necessity of selecting between two evils (except when no choice at all has been offered), has never been too critical of armed power operating in its midst. When Providence has seen fit to make your standard of comfort a wretched one, you accept chastening without complaint; if you must choose between King John and Robin Hood, Robin Hood seems saintly. Sivaji accordingly has been deified,[^19] and not in Maharastra only.

Rise of the Maratha Chieftains

Sivaji’s successors held their Court at Satara and were nominal heads of the Maratha Confederacy. But early in the eighteenth century they fell completely out of sight behind the Peshwa, who was originally Second Minister in Sivaji’s Astha Pradhān. or Cabinet of Eight. The Eight all became hereditary ministers, and to-day the descendants of two are ‘Princes’.[^20] The Peshwa of Shahu, Sivaji’s grandson, secured an outstanding authority, which his son, Baji Rao I, so strengthened that in 1727 he was granted full administrative powers. Henceforward the Maratha Government was in fact the Peshwa’s Government, checked and qualified by the influence of the great semi-independent chieftains.

The Raja of Satara, the Confederacy’s original and nominal overlord, ‘from the mere force of prejudice’ received ‘some occasional attentions’, scrupulously paid him. Enjoying ‘the splendid misery of royalty and a prison’, confined to his capital, on ‘a very moderate allowance’,[^21] he yet formally invested every Peshwa with his khelāt[^22] No Peshwa could take the field without previously taking leave humbly of the Raja. The Satara district possessed a sacred perpetual peace, ‘an exemption from military depredations of all kinds’. When any chieftain entered it he laid aside all marks of his own rank and his drums ceased to beat. Apart from this outward homage, which one of the four great chieftains, the Bhonsla Raja—who claimed to be himself, as Sivaji’s descendant, the true Maratha head—hardly paid at all, the Raja of Satara did not matter in the least but was an empty pageant. The descendants of the Astha Pradhān ministers also, except for the Peshwa, sank into subordinate positions.

Four of the semi-independent military chieftains were of the first rank of importance: the Gaekwar, Sindhia, Holkar, and Bhonsla. They became associated respectively with Baroda, the Ujjain-Gwalior[^23] country, the Vindhya-Narbada country (Indore), and Nagpur-Berar. They were finally established in the third decade of the eighteenth century, but arose a full generation earlier. Their homage therefore went directly to the Peshwa, since in 1727 the Maratha Government became de facto the Peshwa’s Government. The Gaekwar and Holkar and the Bhonsla were very loosely attached to the Confederacy, whose heart was Sindhia and the Peshwa. Gaekwars, Sindhias, and Holkars have survived into modern India as leading Princes—a title which in the eighteenth century they would have disclaimed with formal modesty.

A main source of Maratha strength was that from the first they were catholic in their political and military system and habits. They made use of the fighting qualities of other racial stocks in a manner to which only the Company, with its armies recruited from many castes, could in the late eighteenth century show anything comparable. The English, whose military commanders have been almost usually Scots or Irish and their Prime Ministers and great Cabinet officers often Scots or Jews, were the only enemy whose sinews of war were as elastic as theirs. Sivaji himself had freely employed Muhammadans, as Mahadaji Sindhia did later.

Warren Hastings, who understood most things Indian and possessed an unsleeping curiosity, knew all this. But it came as slow puzzling information to his successors. Lord Wellesley[^24] seems to have been unaware of the Satara family’s existence. He styles the Peshwa a ‘sovereign’ (which, theoretically, he emphatically was not; he was merely a Minister) and throughout his time in India he was under the impression that the Marathas were an ‘Empire’, with a ‘Constitution’ under which Sindhia, Holkar, Gaekwar, and Bhonsla held places like that of himself and his fellow hereditary peers under the British Constitution. It is true that the term ‘Empire’ was used by men better informed than Lord Wellesley, including Arthur Wellesley and Malcolm. But what to them was a term of convenience to him was an accurate description and in the light of his faith that this was so he acted throughout.[^25]

During the latter part of the eighteenth century, Marathas and British had met in desultory fashion, both as friends and foes. The former prowled very far from their home lands and Sivaji’s brother Venkaji established a Maratha dynasty in Tanjore, near Madras. In the casualness of those earliest wars of the Company, a body of Marathas under an adventurer, Morari Rao, fought sometimes against the British, sometimes (as in Clive’s Arcot campaign) on their side.

In 1772, when Warren Hastings lent the Nawab of Oudh a brigade to subjugate the Rohillas, it was well understood that the real menace, behind the Rohillas, was the Marathas. Two years later, in 1774, the Government of Bombay precipitated an iniquitous war with Sindhia and the Peshwa, and achieved thereby the miracle of bringing Hastings and his Council into temporary accord. The latter informed the Bombay Government that its action was ‘impolitic, dangerous, unauthorized, and unjust’, adjectives which were explained and elaborated.

The Gaekwar kept outside this war. So did the Bhonsla Raja, who was always ‘somewhat aloof from the politics of Poona’[^26] and throughout Clive’s and Hastings’ time cultivated with the Company friendly relations, which served the latter well. Holkar, too, can hardly be considered to have taken part in the campaign, which dragged on for several years. In January 1779, the Bombay Government surpassed itself in incompetence, an army surrendering at Wargaon, where its commander signed a convention which, Hastings said, ‘almost made me sink with shame when I read it’. The convention, like that which Roman generals made at the Caudine Forks with a Samnite army, was repudiated, and the Marathas lost their advantage. Hastings, rising to perhaps the highest moment of even his vigorous clear-sighted career, in 1780 thrust out across Central India—into territory almost as legendary in its uncharted immensity as the kingdoms of Prester John or Kubla Khan—two soldiers, Popham and Goddard, who largely repaired the first disasters, though Goddard afterwards lapsed into carelessness that all but brought about a second Wargaon. Two years later (May 1782),[^27] the war ended by the Treaty of Salbai.

This Treaty was important in more ways than one. The Company at last stood out among the Indian Powers, and negotiated on equal terms with one of the two other genuinely independent Powers. The war was recognized as having been on the whole a drawn contest, and it left a conviction on both sides that the sovereignty of India would ultimately be fought out between them, with other Powers merely subsidiaries and subordinates. But for the present both were content with the situation and accepted it without rancour. They had been reasonably good-tempered foes, and Mahadaji Sindhia, who co-operated with Warren Hastings in bringing about a comprehensive and moderate settlement, liked and admired the British leader. He acted as the Peshwa’s representative and also, independently, as guarantor of the treaty. This made him in effect almost a colleague of the Peshwa and left him the leading Maratha chief, a position for which his abilities well qualified him.

III

Decline of Maratha Power

Despite his friendly feeling for Hastings, Mahadaji Sindhia proceeded to strengthen himself with European soldiers of fortune, especially as officers and artillerymen. Most of these were French, that nation being encouraged because of their secular hostility to the English, and also because the latter had the inconvenient habit of commanding their own people to leave a State whenever the Company found itself at war with that State. Their employers thus lost their services when most needed and when they were invaluable to the enemy as spies and intelligence agents. Following a heavy defeat by Sindhia in 1792, Tukoji Holkar, though he distrusted the Western manner of fighting and preferred the predatory Maratha fashion, mobile and sudden and free to pick its terrain, copied his rival in a small way, and began to enlist his own European troops and gunners.

Sindhia found a commander-in-chief in Count de Boigne, whose adventurous career had made him familiar with danger (according to tradition, he had held, among other appointments, the exacting one of lover to the Empress Catharine of Russia). De Boigne added a bayonet to the Maratha trooper’s equipment of sword and target and matchlock, and under this wise leader Sindhia’s armies overran the Rajput States. In 1789, they took Delhi from Ghulam Qadr, an Afghan, who in youth had been castrated by the Emperor and had taken his revenge later by blinding him and holding him captive. Sindhia, ordinarily a merciful man, inflicted a fearful punishment, and reinstated the helpless old Emperor. Shah Alam was treated with respectful kindness by his new protectors, whose elastic polity allowed of many nominal overlords at once. The authority they derived as his deputies and guardians gave a form of propriety to their far-ranging depredations, and they were a people who attached importance to forms.

The Peshwa was an ally of the Company in Cornwallis’ war with Tipu (1790-2), and Maratha contingents rendered good service. But the nation then proceeded to destroy itself, so that Wellesley’s attack in 1803 met a disorganized and weakened opposition. The last decade of the eighteenth century was one of constant clashing of Holkars and Sindhias, of civil dissensions monotonous in repetition and appalling in brutality.

The brutality stands out because, in comparison with the hideous cruelty of contemporaries, European as well as Asiatic, the Maratha record has been generally humane. Their governments, except when actively pillaging, were light; they had little purdah, and their social system as a rule dispensed with the barbaric funeral pomp of Rajput, Sikh, and Bengali, which immolated thousands of women annually.[^28] But during the last decade of the eighteenth century, as one after another every respectable leader passed away, the nation lost its honourable characteristics, including its comparative humanity. On occasion, especially under the last Peshwa in Poona, Maratha executions vied in cold-blooded ferocity with the worst of other lands.

Mahadaji Sindhia died in 1794, and was succeeded by his grand-nephew Daulat Rao Sindhia, in every way his inferior. Daulat Rao in 1798 married a girl of great beauty, with whom he was infatuated, and fell completely under the influence of her father, Sarji Rao Ghatke, the evil genius of the Maratha nation.

The Sindhias’ great rivals, the Holkars, less ostentatiously wicked, were also weaker in resources. Their celebrated Princess, Ahalya Bai, venerated in her life as nearly divine and after her death deified,[^29] died in 1795, and her chief captain and minister, Tukoji Holkar, died two years later. The time’s confusions quickly eliminated the elder of the latter’s two legitimate sons. Two illegitimate sons, who were brothers, questioned the title of the remaining legitimate son, who was imbecile in mind and body and lived only to express a steadily developing viciousness, in which Ghatke and Sindhia encouraged him. The Holkars were soon reduced to the level of fugitive robber chiefs.

Meanwhile, the Peshwa’s authority also sank to vanishing point. In 1795, Madhu Rao Narayan, whom Balaji Janardan Farnavis (Fadnis), best known as Nana Farnavis, the greatest Indian statesman of the later eighteenth century, kept in surveillance that was practically incarceration, either flung himself from a balcony or fell accidentally, to die of his hurts, 27 October. A puppet Peshwa who reigned from June to November of the next year was deposed after a brief period of confusion and intrigue and counter-intrigue, and Baji Rao II, cousin of the Peshwa who had died, was established by consent among the chieftains.[^30] His father, Raghunath Rao, had been a protégé of the British and indeed the main cause of the First Anglo-Maratha War in Warren Hastings’ time, which was brought about by his claim to the peshwaship. Baji Rao was distrusted from the first; the Maratha leaders, and Nana Farnavis most of all, always suspected him of readiness to accept a position of dependence under the Company. A youth of ingratiating presence but extreme timidity, he was crammed to the recesses of his personality with faithlessness and cowardice.

Henceforward the Maratha Confederacy was shaken by incessant quarrels and by civil war made lurid with sadistic executions. Dissatisfied with the ordinary methods of blowing from a gun and trampling by an elephant, Sarji Rao Ghatke invented such deaths as tying to red-hot cannons and festooning with rockets that carried the victim along in a whirl of explosions. As the century ended, Sindhia and Yeswant Rao Holkar, the abler of the two illegitimate Holkar brothers, marched and countermarched, fighting a series of battles, of which some of the fiercest took place when they were nominally at peace. The vast extent of territory which the Marathas occupied was swept with storm-winds, as if it were the playground of demons. China in our own day endured a similar misery under its warlords, whose frivolous contests led to the coming in of Japan.

Hyderabad and the Battle of Kharda

There was only one quiet interlude, when Nana Farnavis took advantage of the retraction and retrenchment enforced on the East India Company by the cost of Lord Cornwallis’ campaign against Tipu. He accomplished the singular feat of bringing the Maratha chieftains together against the Company’s protégé, the Nizam of Hyderabad. This was the last occasion when they all appeared under the Peshwa’s authority.

Hyderabad, which to-day is recognized as in a class apart from the other Indian States, its ruler styled His Exalted Highness and Britain’s Faithful Ally, attained this distinction entirely by the fact that it became very early a tulchan kingdom, straw-stuffed and held upright by the Company, except for a very brief period of forgetfulness, when a whiff of hostility from the Marathas was allowed to blow it down. Unlike the Marathas, the State had neither racial nor religious cohesion. It was the creation of one able man, Asaf Jah, the Emperor’s Wazir, who in 1724 withdrew to it as Subadar (‘Overseer’) of the Deccan and freed himself from all but nominal dependence on his master, in the same period as that in which the leading Maratha chiefs established themselves. He and his successors are generally styled Nizams, from his title Nizam-ul-mulk, ‘Regulator of the State’. He died in 1748, and in the stormy days that followed Hyderabad was saved only by the coming of the British.

As the century neared its finish, the Nizam was very conscious that he was much the weakest of the four leading Powers of India —the others being Tipu, the Marathas, and the Company—and by long subservience had come to lean heavily on the British. Lord Cornwallis’ successor, Sir John Shore, had neither the money nor the inclination for campaigns, though aware that the Nizam would have liked assistance in settling his differences with the Marathas. ‘If I were disposed’, he wrote,[^31] ‘to depart from justice and good faith, I could form alliances which would shake the Mahratta Empire to its very foundations.’ He refused to depart from justice and good faith and to give assistance. It is customary to blame Shore for the defeat which overtook the Nizam, but this is to judge the former’s actions through the eyes of Wellesley and of those who followed Wellesley.

For the Marathas were still in Shore’s day what they ceased to be after 1803. They were genuinely independent. They held that the Nizam’s relation to them was that of the Nawab Wazir of Oudh to the East India Company, that he was a protected dependent tributary chieftain. By treaty he had acknowledged their right to levy chauth and deshmukh[^32] and to send their officers to collect these dues in his territory. Malet, in August 1794, wrote of his dominions as in a condition of’dependence and thraldom’ and of the Marathas’ authority as being ‘enforced by their officers under a variety of demonstrations throughout his country’.[^33] Shore felt he had no choice but to stand strictly by the letter of treaties, by whomever made. The Nizam therefore appeared to him as a defaulter who was trying to evade plain obligations. His record towards the Company had long been one of duplicity, and when he sent a desperate last-minute appeal his own State on merits seemed little entitled to help, as ‘incorrigibly depraved, devoid of energy . . . consequently liable to sink into vassalage’.

The Nizam, disgruntled at his temporary desertion by his friends of the East India Company, followed Maratha example. He turned to the French and obtained his own Foreign Legion. But before his measures were matured Nana Farnavis in 1795 brought the long-standing dispute to the arbitrament of battle, which was boastfully accepted. Dancing girls sang the Nizam’s expected triumph. Court buffoons were witty about it and his chief minister predicted that the Peshwa would be sent, with a cloth round his loins and a brass pot in his hand, to mutter incantations on the bank of the Ganges at Benares. There was one battle only, at Kharda, where his troops fled in dastardly fashion. The fight, apart from the pursuit, was won and lost as cheaply as Plassey. The victorious Peshwa went forward from it with downcast demeanour, which he explained as due to shame on both his enemy’s account and his own people’s, that the one should have yielded so contemptible a conquest and the other should consider it worth exulting over. The Nizam was mulcted of an indemnity, but was not treated harshly.

Helpless and humiliated, he was the destined dependent of whichever of the really great Indian Powers first troubled to demand his allegiance. The Marathas took little interest in him, and Tipu was too busy preparing for his own final struggle. It was therefore the British who reclaimed their strayed associate. Raymond, the much loved Commandant of the Nizam’s French soldiery, died, and Lord Wellesley, recently arrived in India, at once (October 1798), as a preliminary to his attack on Tipu, seized the event as excuse and occasion for ‘the expulsion of that nest of democrats’ whom Raymond had gathered. The Nizam was half cajoled, half bullied, into disbanding his foreign auxiliaries. He was drawn back into alliance, and a treaty and a subsidiary force were clamped down on his State.

When the final war with Tipu began, four months later, Hyderabad was not a large State. But when war ended its boundaries were extended by the Nizam’s acceptance of territory offered first to the Peshwa, on terms which he refused. They were extended again, another four years later, after the Second Anglo-Maratha war. Hyderabad to-day is as large as France, but no State can ever have combined such material importance with so undistinguished a record and so fictitious an independence, until comparatively recently.[^34]

Its importance was trivial in the extreme, and its independence completely fictitious, in the half century before the Mutiny, and perhaps most of all in Lord Wellesley’s time. No one deviated from an attitude of steady contempt for it. Though Hyderabad was the Company’s nominal ally against the Marathas, as against Tipu, Arthur Wellesley considered that it was ‘impossible for persons to have behaved in a more shuffling manner’.[^35] The tergiversations of the Nizam’s Government were a large part of the experience which led him to his conclusion, that events

‘ought to be a lesson to us to beware not to involve ourselves in engagements either with, or in concert with, or on behalf of, people who have no faith, or no principle of honour or of honesty, or such as usually among us guide the conduct of gentlemen, unless duly and formally authorized by our government.’[^36]

Baroda and the Gaekwar

Nana Farnavis’ long unchallenged reputation as a statesman is being at last questioned by historians of his own nation. But it can hardly be questioned that he was right in his unswerving effort to give the Marathas a focus and head, and to make them a confederacy under the Peshwa and based on Poona. No one but the Nana could have secured the Gaekwar’s assistance in the Kharda campaign. Since the Treaty of Salbai, in 1781, which closed a war in which the British had supported him against Sindhia, the Gaekwar’s had been practically a protected State of the Company.[^37]

The Gaekwar’s subsequent relations with the British and with his own people for the sake of convenience can be briefly summarized here. After Kharda, he practically withdrew from the Maratha Confederacy. In 1799, when the Company annexed Surat, he was requested to make this acquisition more worth while, by handing over an adjacent district. He consented, but remarked that the Peshwa’s sanction should be obtained. Both parties were aware that the Peshwa was in no case to refuse (which he would have done if free to do so). All he could do was to rebuke his straying and now all-but-emancipated vassal for concluding a separate treaty with the Company. The rebuke went unheeded; the Gaekwar was conducting a private war with the Peshwa’s Governor of Ahmadabad, and hoped to get British help. He did not get it, but managed to succeed without it. In September 1800 he died, and Baroda was involved in civil war, which the British were asked to settle, both parties making the Bombay Government tempting offers.[^38] The Bombay Government settled it accordingly, by another of the toy campaigns with battles costing two or three score casualties, which are so many in British-Indian history that they have deservedly dropped from sight. After one of these victories, in which between 5,000 and 6,000 men, of whom over 2,000 were Europeans, suffered ‘the very considerable casualty list of 162’[^39] (104 being Europeans) or something less than a thirtieth of their force, the General of the claimant whom the Company was supporting wrote with perhaps excessive enthusiasm (but it gives us the measure of the martial ardour which in nine cases out of ten was all that the British had to overcome): ‘I was quite astonished to see the manner in which the English fought. I do not suppose anybody in the world can fight like them.’

The new Gaekwar, when the fighting was over and his enemies chased out of their fortresses, accepted a subsidiary force (25 June 1802), and one of the four great chieftains had been permanently detached from the Maratha confederacy. The British Resident, Major Walker, became practically ruler of Baroda, whose finances and administration were in ruins,[^40] and the Gaekwar’s dominions subsided into something strangely like peace. Henceforward, the troubles which for twenty years came thick and fast upon his brethren were probably interesting news items to him, but they were nothing more. The other Marathas continued to be like the sea, that is never at rest. But he himself had said good-bye to all that, and was emeritus from it.

Count de Boigne, the maker of Sindhia’s army, retired in 1796, the year after Kharda. A French gentleman of pre-Revolution type, he hated new-fangled ideas of liberty, fraternity, equality, and was well disposed to the Company, whose commission he had once held. He left Sindhia, as his last word, his reiterated warning that he would do well not to excite British jealousy, and that it would be better to disband his battalions than to fight. The Company showed de Boigne every courtesy in his journey from India to Europe, and arranged the transference of his vast fortune[^41] to his native city, Chambéry, in Savoy. Here he lived with great distinction until his eightieth year, in 1830—a ‘nabob’ who dispensed lavish charity to his fellow-Savoyards. He was always ready to talk over Indian affairs with British visitors, and to express his poor opinion of his successors in Sindhia’s higher command.

He was followed by General Perron, and the Ganges-Jumna doab, assigned for the upkeep of the French officers and their sepoys, was presently styled, by Lord Wellesley, Perron’s ‘independent state’, and his 30,000 troops ‘the national army’ of that state.[^42] Tipu’s downfall, however, had already come as a knell to the dreams of recovering India, which France had cherished through three decades of failure and growing weakness. A handful of foreign mercenaries could make no difference to what destiny had settled.

IV

Lord Wellesley and the Peshwa

Lord Wellesley on reaching India had found the Peshwa’s authority ‘reduced to a state of extreme weakness by the imbecility of his counsels, by the instability and treachery of his disposition, and by the prevalence of internal discord’. He set himself to obtain through him complete control of Maratha affairs.

For a while he was foiled. His intended agent

‘deliberately preferred a situation of degradation and danger with nominal independence, to a more intimate connection with the British power, which could not be calculated to secure to the Peishwa the constant protection of our armies without at the same time establishing our ascendancy in the Mahratta empire.’[^43]

In a torrent of exasperation Wellesley—whose language is a laval flow that never cools, fed by incessant renewal from the internal fires—ascribed to his opponent ‘intricacy’, ‘perverse policy’, ‘treachery’, ‘low cunning’, ‘captious jealousy’, ‘the spirit of intrigue and duplicity inseparable from the Mahratta character’. With all this he contrasted his own ‘just and reasonable’, ‘temperate, and ‘moderate, proposals. He found the contrast maddening and the obstinacy which refused to fall in with his plans for a new order in India insupportable.

The Marathas had been distinguished among the ramshackle polities of India by a genuine patriotism which operated despite their dissensions. But their dissensions had now become too deep-seated for healing. In the warfare which followed with the British they were hopelessly outclassed in every phase, the diplomatic no less than the military.

Their carelessness as regards military intelligence was impossible to exaggerate, and was to increase a disparity which was immense already in equipment and organization. As Sardesai points out, while every British officer who toured their country used his eyes and afterwards his tongue and pen, and while a number of British could speak and understand Marathi, the Marathas ‘knew nothing about England, about the British form of Government, about their settlements and factories . . . their character and inclinations, their arms and armaments; perhaps even Nana Fadnis did not at all possess such details . . . the Marathas were woefully ignorant.’[^44] Even Nana Farnavis ‘was ignorant not only of the geography of the outside world, but even of India. The maps which he used in those days are extant and are fantastic, inaccurate and useless.’

As against this, the East India Company’s Secretariat was served in the courts of Native India by a succession and galaxy of men such as even the British Empire has hardly ever possessed together at any other time. ‘Their spy system was perfect.’[^45] As a consequence, when war broke out in 1803, the Marathas, sprawling in their desultory fashion over half of India, had been tracked down over a score of years past, and their habits, their strength and weakness, scientifically docketed. Lord Wellesley’s files contained information gathered as far back as 1779, in G. W. Malet’s elaborate report[^46] on the Sindhia and Holkar families and their history, when he was stationed at Surat. The same cool indefatigable observer, when attached to the Maratha camp before Kharda, had added, in March 1795, a fascinating analysis of his hosts’ military methods or want of method. No one considered such reports to constitute espionage or any breach of hospitality. ‘I consider it as the duty of every British subject in this country, however situated, to contribute to the utmost of his power, to the stock of general information.’[^47]

Colonel William Palmer, who succeeded Malet as the Company’s representative at Poona, was urged unceasingly to watch for the chance to establish British ascendancy over the Peshwa and through him over all the Marathas. Like Major Kirkpatrick, his colleague at the Nizam’s court, Palmer was Indianized in habits and sympathies, and he carried out tactfully instructions which were couched in terms of excitement and exacerbation. Nevertheless, the Peshwa, though even his suspicious mind could hardly have guessed what close continuous studies of his conduct and intentions[^48] were being passed to the Governor-General, felt like a wild beast of the jungle, when hunters are behind all bushes. Not the Peshwa alone, but Sindhia, the Bhonsla Raja, and Holkar, all ultimately behaved in a manner which put them at a complete political, as well as military, disadvantage and gave their adversary ample justification by his own standards of thinking to hold them up to indignation, as morally responsible for the outbreak of hostilities. To achieve this is a large part of what has always been considered statesmanship, in every age and land. It has rarely been achieved more triumphantly than in India, in the twenty years when Independence was lost. Maratha statecraft was casual and occasional, meeting the immediate demand with what appeared to be the best immediate answer, which was often an evasive one. These answers were taken up, explored, replied to, and filed by a Secretariat which had been stiffened into the sternest efficiency—a machine that lost account of nothing, but tabulated and kept and compared all that came into it, and drove remorselessly to its foreseen end. Sir Thomas Munro quoted with agreement and approval a remark made by the Maratha patriot Moro Pant Dikshit, to his friend Major Ford, in 1817, that ‘no Native Power could, from its habits, conduct itself with such strict fidelity as we seemed to demand’.

It was the final campaign against Mysore which brought relations to their first crisis. When hostilities were about to break out, Lord Wellesley reminded the Peshwa of an agreement which bound the Company, the Nizam, and the Marathas in alliance, in the event of one of them being at war. The Peshwa procrastinated, and intrigued with Tipu;[^49] his assistance never materialized until all fighting was over, when his troops took the field with superfluous alacrity and overran the north of Mysore. Wellesley was incensed; having a uniformly high esteem for his own sentiments, he was never at any pains to hide them, and was at none now. He nevertheless offered the Peshwa some of the territory of conquered Mysore—on terms which offended, so that the offer was not accepted, although the Governor-General had been at pains, according to his lights, to be entirely reasonable, hoping to find the Peshwa reasonable also, with his eyes not fixed on that gaudy toy, Independence. The Resident at Poona was instructed, 23 May 1799:

‘Although the Peishwa’s conduct . . . has been such as to forfeit every claim upon the faith or justice of the Company, I have determined to allow him a certain share in the division of the conquered territory, provided he shall conduct himself in a manner suitable to the nature of his own situation and of that of the Allies. . . .’[^50]

Three weeks later, Palmer was told to notify the beneficiary

‘that it is my intention under certain conditions, to make a considerable cession of territory to him, provided his conduct shall not in the interval have been such as to have rendered all friendly intercourse with him incompatible with the honour of the British Government. You will be careful in whatever communications you shall make on this subject to apprize the Peishwa that he has forfeited not only all claim to any portion of the conquered territory under the terms of the triple Alliance, but also under those of the declaration which I authorized you to make in my instructions of the 3rd of April. I wish, however, that the general tenor of your communications to the Peishwa should be of a conciliatory and amicable nature. . . .’[^51]

The conditions attached were, that the Peshwa should accept a British force at Poona and employ no more Frenchmen; pledge himself to alliance if the French invaded India: and accept unconditionally the Company’s arbitration of all disputes outstanding between him and the Nizam, and of all future disputes. In fine, that the Maratha confederacy should consent to abrogation of its independence and to inclusion in the British subsidiary system.

The Subsidiary System

The mischief which this system did to the States on which it was imposed, and its intensification of their people’s sufferings, were clearly seen, frankly admitted, by the men who imposed it. With a new invincible force behind him, the most intolerable Prince was placed above the reach of complaint. Let the mildest of the Duke of Wellington’s many comments be cited. Subsidiary troops, he wrote,

‘are to oppose foreign invaders and great rebels, but are not to be the support of the little dirty amildary exactions. It is, besides, very disadvantageous and unjust to the character of the British nation, to make the British troops the means of carrying on all the violent and unpopular acts of these Native governments, such as, for instance, the resumption of the jaghires of the Mussulman chiefs in the Soubah’s countries.’[^52]

Sir Thomas Munro testified:

‘There are many weighty objections to the employment of a subsidiary force. It has a natural tendency to render the government of every country in which it exists weak and oppressive; to extinguish all honourable spirit among the higher classes of society, and to degrade and impoverish the whole people. The usual remedy of a bad government in India is a quiet revolution in the palace, or a violent one by rebellion, or foreign conquests. But the presence of a British force cuts off every chance of remedy, by supporting the prince on the throne against every foreign and domestic enemy. It renders him indolent, by teaching him to trust to strangers for his security; and cruel and avaricious, by showing him that he has nothing to fear from the hatred of his subjects. Wherever the subsidiary system is introduced, unless the reigning prince be a man of great abilities, the country will soon bear the marks of it in decaying villages and decreasing population.’

He considered that ‘the simple and direct mode of conquest from without is more creditable both to our armies and to our national character, than that of dismemberment from within by the aid of a subsidiary force’. ‘If the British Government is not favourable to the improvement of the Indian character, that of its control through a subsidiary force is still less so.’ It was bound to bring war.

‘Even if the prince himself were disposed to adhere rigidly to the alliance, there will always be some amongst his principal officers who will urge him to break it. As long as there remains in the country any high-minded independence, which seeks to throw off the control of strangers, such counsellors will be found. I have a better opinion of the natives of India than to think that this spirit will ever be completely extinguished; and I can therefore have no doubt that the subsidiary system must everywhere run its full course, and destroy every government which it undertakes to protect.’[^53]

Of the corruption and tyranny that the system inevitably brought in its train, such witnesses as Metcalfe and Sutherland may be consulted passim.

For the Company, however, the system held immense advantages. By its means the Governor-General was present by proxy in every State that accepted it. Well-trained bodies of troops were dotted about in strategic and key positions. Their officers were exceptionally highly paid, and formed a notable addition to the Company’s patronage. The whole cost fell on Native Governments which meanwhile sank into emasculation, relieved of the necessity to protect themselves, and with their rulers safeguarded against any danger arising from discontent. Finally, the system ‘enabled the British to throw forward their military, considerably in advance of their political, frontier’,[^54] and kept ‘the evils of war . . . at a distance from the sources of our wealth and our power’.[^55]

If war came, ‘hostilities’, Metcalfe noted in 1806, ‘are carried far from our territories, and we still enjoy the advantages of a friendly country in our rear’.[^56] We ourselves, in three continents, have learnt most painfully in recent years, how great are the conveniences of waging a campaign on others’ soil and sparing our own; also, how effectively states can be disrupted from within.

V

British and Maratha Diplomacy

Nana Farnavis foresaw his countrymen’s subjection. He ‘respected the English, admired their sincerity and the vigour of their government; but, as political enemies, no one regarded them with more jealousy and alarm’.[^57] While he lived he warded off their suzerainty, without exasperating Lord Wellesley or losing the respect which the Governor-General accorded to him alone. His chief weapon was a disconcerting frankness. ‘A man of strict veracity,’^58 he answered questions freely, and gave explanations which (Palmer points out repeatedly) tallied exactly with information received and checked up from other sources. ‘Humane, frugal, and charitable,’ he wore himself out in what he well knew was a vain effort to prevent the inevitable.[^59] ‘His whole time was regulated with the strictest order, and the business personally transacted by him almost exceeds credibility.’

The Governor-General’s irritation was fiery, when under this wary guidance the Peshwa parried his proposals. He saw himself offering a pigmy eternal security, and honourable alliance with a giant. The response he characterized as ‘vexatious and illusory discussion’, ‘temporizing and studied evasion’.

It was undoubtedly all this, and in fairness it must be noted that the British were not the only critics of the Marathas. Bussy complained (9 September 1783) that the French representative at Poona, while showing zeal and disinterestedness, had placed ‘trop de créance aux protestations et au discours d’une peuple inconstante et perfide’.[^60] Their replies were no replies, or put forward to gain time or postpone a decision. It was a warring of different ethics and habits, and not of armies only. And when war came in 1803 (with the Peshwa nominally allied with the British) the Governor-General had this much excuse for his feeling of outraged blamelessness, that at one time or another every Maratha leader, including even Holkar, had sounded his agents on the chances of getting Company support.

We can to-day see that neither side was as villainous as the partisans of either assume. Sir William Foster’s words, of Sir Thomas Roe’s attempts to get an agreement out of the Emperor Jahangir nearly two centuries before, are equally true of Wellesley’s negotiations with the Marathas: a treaty on Western lines was ‘an idea utterly alien’ to their political system.[^61] On the other hand, Wellesley never made the slightest effort to understand that system and to work with it. Unable to envisage any kind of state other than those known in Western Europe, complete with orderly and methodical chancellery and secretariat, he simply could not see how casual and desultory Maratha methods were. He declared frankly that he considered incorporation into the Company’s dominions the greatest blessing it was possible to confer on the peoples of India. Failing this, he would have standardized India into something approaching English conditions; the Princes should be great hereditary territorial magnates, with detachments from the British army acting as their special police to suppress subversive ideas and persons. He saw some kind of ‘Prince’ in every chieftain who looked belligerent enough. He offered every such chieftain a place in the Company’s family; his titles should be confirmed, and his weapons taken over (on payment). H. St. G. Tucker, his Accountant-General, looking back on this period, wrote in 1814:

‘As for subsidiary treaties, I am sick of the very term. Lord Wellesley was for firing off these treaties at every man with a blunderbuss.’[^62]

Wellesley therefore misunderstood inquiries, which the Marathas meant as merely requests for a friendly ‘accommodation’ during temporary embarrassment, as solemn applications for a position which he was only too eager to force upon them. When Sindhia or the Peshwa found himself falling back, after some disastrous bout with Holkar—or when Holkar was fleeing to his Vindhya fastnesses—the warrior whose fortunes were at stake took more than a solely intellectual interest in the chances of borrowing a few companies of well-drilled sepoys. This was undoubtedly true. But he was certain to want afterwards, when the crisis was over, to dismiss these auxiliaries (if he had obtained them) with good will and gifts. He certainly did not want them except as a very present help in time of trouble. The political seesaw went up and down too swiftly for even a rout to be cause for despair.

‘When the Devil was sick the Devil a monk would be.

When the Devil was well the Devil a monk was he!’

Moreover, for even this modified and temporary repentance the sickness had to be severe.[^63] The Marathas had fought for generations to avoid submission to the Mogul Emperors; to Lord Wellesley it appeared strange that they should be unwilling to come under the mild regimentation of a Power that had come from Europe. But there it was. There was no searching of the heart of man, especially Asiatic man; it was full of deceit and desperately wicked and foolish. Nothing but necessity would make the Peshwa accept a subsidiary treaty and a Company’s armed force. With increasing exasperation the Governor-General came to realize this.

Lord Wellesley’s Dealings with Minor States

Not merely the Governor-General’s tone, his actions frightened the Peshwa. In 1799, he annexed Surat and Tanjore, tiny principalities far apart. The suppression of Surat has called out a remarkable agreement of condemnation by historians, but is not of sufficient importance for more than mention here. Wellesley took it, on its Nawab’s death, on the ground that in that part of India, and towards Surat in particular, the Company had stepped into the Mogul Empire’s shoes, and inherited its right to dispose of dependent semi-regalities. Tanjore, an outpost which the Marathas had established during their wide wanderings, he took because it was perhaps the worst misgoverned of several states which European financiers had long pillaged. Also in 1799, Wellesley in a paroxysm of wrathful energy tried to force the Company’s dependent during forty years, the Nawab of Oudh, to surrender his dominions, and all but succeeded. In 1801, he did extinguish the title and authority of the Nawab of the Carnatic, in whose name the Company had originally become one of India’s martial powers, in 1747. The Marathas noted these happenings and the doctrine which justified them. As by a miracle, the Company had just failed to thrust an encircling arm along their northeastern borders, in Oudh, and it was now in undisputed possession of all south India.

As for the menacing tone in which the Governor-General offered the Peshwa a slice of Mysore territory, it was the tone he habitually used with everyone, and it is unique, even in a record which includes Dalhousie and Curzon. He never caught even the most fleeting glimpse of any point of view but his own, which was always pikestaff plain and crystal-clear to him, so that to differ was to equivocate and to merit instant crushing. Wellesley lay down, slept, and awoke always the Governor-General, shaken from his dreams into a world of men and women calling for constant oversight and sharp correction. No novelist would dare to invent such a style of correspondence for one of his characters; he would be told that no person could ever be so humourlessly oppressed with his own towering importance and undeviating rectitude. Nevertheless, Lord Wellesley was. The Directors’ recall of him is censured as injustice to a great man. The marvel is that, being human, they endured him so long.

By his own people, this manner was received variously. The very young, and the army generally, admired it intensely, and the Royal Tiger, as he styled himself, lived in a buzz of adulation, and was ‘the glorious little man’.

Much of this adulation was sincere. We still feel strongly the prestige of rank. The early nineteenth century felt it much more. Men went to India in their teens, often at an age when they would now be still at their preparatory school. Boys flung out thus felt no inclination to criticize a nobleman of the vigorous decision and self-sufficing grandeur of Lord Wellesley. He made the times exciting and splendid. War, war, more war—against Tipu now, then against Dhundia Wagh and the Nairs, then against Sindhia and the Bhonsla, then against that rascal Holkar! ‘Victory huddling on victory’—Periapatam, Malaveli, Seringapatam, Aligarh, Delhi, Laswari, Ahmadnagar, Assaye, Argaon, Gawilgarh, Dig, Farakhabad! How sick the French must be, and that little reptile Buonaparte most of all! Nelson had crowned the British name with glory at the Nile. But their own glorious little man was adding kingdoms like a boy gathering apples. He was directing campaigns which meant prize-money, new territories to be administered, new princes as dependents, triumph and everlasting fame. And those cheese-paring Directors grumbled about expense!

But as you study contemporary memoirs and letters you become aware of a reticence, and almost a sense of conspiracy, among the men who were ten years older than the schoolboys[^64] who surrounded the glorious little man—the men who were in the late twenties and early thirties, and who did the actual conquering and administering. The Englishman of thirty in India is a veteran, even to-day. In the eighteenth century, he was almost an old man. John Malcolm had appeared for his ensign’s commission when twelve years of age. ‘Well, little man, and what would you do if you met Haidar Ali?’ he was good-humouredly asked. ‘I’d cut aff his heid’, said the ferocious child; after the burst of laughter had subsided, he was told he would do. Three years later, Major Dallas in a Mysore mountain pass met two companies of sepoys marching behind a red-faced lad on a rough pony, and asked him for the commanding officer. ‘I am the commanding officer’, answered Malcolm. When Lord Wellesley reached India, Malcolm was twenty-nine, and more than half his life had been years of service. He, too, cursed the Directors’ craze for economy, but not solely because it hampered the waging of glorious wars (though Malcolm could be enthusiastic enough about these). Wars were something which he and the men of his rank in the service waged themselves, and not by proxy; and war was not their only interest. Malcolm wanted money for other than martial uses only.

Away from Calcutta, on the Mysore front or wherever Company’s troops were massing against the Marathas, were these men —Malcolm, Munro, Close, Webbe, Graeme Mercer, Arthur Wellesley himself—who knew from daily experience that conquest was not the matter of a few maps on a table and an excited walking to and fro and dictating orders and despatches. There were districts too starving or depopulated to furnish supplies on demand: there were anxieties about transport or rivers too swollen to cross. There were, they discovered, two sides to some questions. Sometimes the enemy or potential enemy had a case; sometimes, on personal acquaintance, he was not the boor or savage that he was previously reported. They sometimes thought a proposed war unjust, or at least an unduly hard measure.

But it was no use saying this to the glorious little man in his Council Chamber in far-off Calcutta. He had exploded on to Indian shores like a tempest, full of fury at the low manners and vulgarity of the society he found there. He described himself, in letters to his peers in England, as stalking solitary like a Bengal tiger, ‘without even a friendly jackal to soothe the severity of my thoughts’. This promising beginning he kept up through a correspondence which for voluminousness is matched only by Warren Hastings’. What justification there was for its tone, in the general turpitude to which he testified, we can guess only; the Duke of Wellington said there was hardly a good-tempered man in all India. But contemporaries were soon telling each other stories to illustrate their common terror;[^65] and one and all, for the tiniest deviation from conduct which their master thought the right one, were overwhelmed with majestic scoldings. His Commander-in-Chief, a man far older than he, on occasion grovelled in abject abasement. One of his brothers, Henry, acted as the Governor-General’s Private Secretary, and another, afterwards the celebrated Duke of Wellington, was advanced swiftly over the heads of senior officers, until he commanded the southern of the two great armies in the Maratha War of 1803. But they and the Governor-General never wavered into real friendliness; Henry and Arthur preserved intact a wary discretion. There clings to their relationship with one another and with other officers more than a little of the atmosphere of schoolboy friendships cemented under adversity and the overhanging threat of watchful Authority.

We must then be aware of two groups operating simultaneously. There was the Governor-General’s immediate circle, to whom he was a good though stern master; typical of them was young Charles Metcalfe, in whose eyes Lord Wellesley could do no wrong, and whose gratitude for exceptional and consistent kindness is as clear as his perception that in sense of duty and public and private honour the Governor-General was outstanding. There were also the older men doing the actual fighting and administering, who remained rigidly reserved towards the Governor-General, while writing and talking freely amongst themselves, if in subdued tones. It is a very striking picture, and it has been twice repeated in India, though never with the completeness of contrast in Wellesley’s time. Wellesley went through his term of office, learning nothing, and never suspecting the immense caution he enforced on those who might have enlightened him.

He had great qualities, and among them was a real and unwavering liberality, by the time’s standards, of political thought. But our concern is with his political actions only.

VI

The Death of Nana Farnavis

Matters cannot last long as they are at Poonah: the Peshwah’s Government must either fall to pieces or he must accept our support. If he should still be obstinate, out of his ruins some power may be formed whose authority it may not be difficult for us to secure and afterwards to enlarge to such a degree as we may think proper.

— Arthur Wellesley, 19 November 1799.

While Nana Farnavis continued to deflect the Governor-General’s invitations to bring the Marathas into the subsidiary system, nothing could be more fantastic than the picture presented by Madras or by the vassal States of Oudh and Hyderabad, a seething delirium of misery. In comparison, the regions where the Nana governed were an oasis of gentle security.

Yet even their bliss was strictly qualified; the fact that they were considered happy testifies to the lunatic disorder of the Indian scene. Malcolm, journeying from Poona to Bombay, in 1799, fell in with a small guard leading a young man whose hands were bound:

‘I asked them who the prisoner was, and where they were going. The commander of the guard said they were going about a mile further, to a spot where a robbery and murder had recently been committed. “And when there,” he added, “I shall cut this man’s head off.” “Is he the murderer?” I asked. “No,” said the man, “nor does he, I believe, know anything about it. But he belongs to the country of the Siddee, from which the murderers, we know, came; and we have orders, whenever an occurrence of this nature happens, to proceed into that country and to seize and put to death the first male who has arrived at years of maturity, that we meet. This youth,” he concluded, “was taken yesterday, and must suffer to-day.” On my expressing astonishment and horror . . . he said that he only obeyed orders. “But,” he continued, “I believe it is a very good plan. First, because it was adopted by Nanah Furnavese, who was a wise man; and secondly, because I am old enough to recollect when no year ever passed without twenty or thirty murders and robberies on this road, and all by gangs from the Siddee’s country. Now they are quite rare; not above four or five within these twelve or fifteen years, which is the period this custom has been established.”