Poet and Dramatist

Book I. 1861-1886. Early Life and Poetry

- Prolegomena

- Early Days

- Juvenilia

- The Heart-Wilderness

- Emergence: Dramatic Beginnings

- Last Poems of Youth

Book II 1887-1897. The Shileida and Sādhanā Period

- Maturity

- Poems on Social Problems

- First Dramas of Maturity

- Residence at Shileida

- The Jībandebatā

- Last Dramatic Work of the Sādhanā Period

- The Last Rice

Book III. 1898-1905. Unrest and Change

Book IV. 1905-1919. The Gitānjali Period

- Growing Symbolism—New Dramas

- The Second ‘Emergence’, into World Reputation

- Phālguni. Nationalism and Internationalism

Book V. 1919-1941. Internationalism

Appendix

‘The exchange of international thought is the only possible salvation of the world.’

— Thomas Hardy‘One may then laudably desire not to be counted a fool by wise men, nor a knave by good men, nor a fanatic by sober men. One may desire to show that the cause for which he has lived and laboured all the best years of his life is not so preposterous, intellectually and morally, as of late it has been made to appear by its noisier and more aggressive representatives; that he has never been duped by the sophistries and puerilities of its approved controversialists, but has rested on graver and worthier reasons, however ill- defined and ill-expressed; that even if his defence of it should have failed, he has not failed in courage or candour or sincerity; nor has he ever wittingly lent himself to the defence of folly or imposture.’

— George Tyrrell, Through Scylla and Charybdis, viii.

To

Rani and Prasanta Mahalanobis

Kindest and most unselfish of friends,

courageous and steadfast through the

years, loyal through all detractions and

anger

Preface

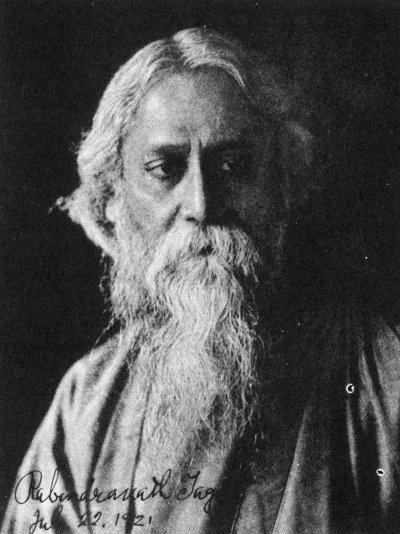

Over twenty years ago, I published a short study, Rabindranath Tagore, then, in 1926, a quite different longer book, Tagore, Poet and Dramatist; both have long been out of print. It is the later book which is now brought up to date with the poet’s death.

A book, as someone has observed, never completely shakes off its first draft, and my own opinions and critical judgements have changed very greatly. But rewriting has been drastic enough (some 35,000 words have been excised, and much added and changed) to make this in essentials a new examintion, and a reasonably close representation of what I now feel. I have remembered always that Tagore (though his work, having to get past the concealment of an Indian language, came to judgement in the age of the First World War and of T. S. Eliot) as a writer was the contemporary of the later Tennyson and Browning and of Robert Bridges. In fairness, he must be judged as the Victorian poets are judged, whose world has passed away.

Milton’s English verse is less than 18,000 lines. Tagore’s published verse and dramas amount to 150,000 lines or their equivalent. His non-dramatic prose, novels, short stories, autobiography, criticism, essays of many kinds, is more than twice as much, and there is also a mass of uncollected material. I make no apology for omissions. Paper stocks are rationed, and the poet’s Bengali admirers, who may feel disappointment that favourite pieces are not mentioned, must accept my assurance that I have cut down ruthlessly from necessity. I have also cut out my bibliography. I think mine was the first, but a bibliography is of value chiefly to students of Bengali literature; I have only 350 titles, and an inclusive list is in process of compilation. My own work is nearly finished, and I am able to do, not what a younger man might do but only what is still possible.

We ourselves know little of India, while Indians know a great deal about us and even about our innermost thoughts. Of what we have hardly cared to know, yet which many are at last anxious to know, there is evidence enough if we take some trouble. Gandhi’s uniquely frank revelation of his ‘experiments with truth’; Jawaharlal Nehru’s Autobiography, which carries the impress of his candour and integrity; and Tagore’s writings and public activities—if we know these now these, we are not likely to be surprised by events as they presently unfold. ‘Norway breaking from thy hand, O King’, answered Einar Tamberskelve at the Battle of Stiklestad, when Olaf turned inquiringly at the snapping of his bowstring. After the lapse of a millennium, the world heard a sound as full of meaning, from Singapore and Burma. There will be no restoration of the empire we have known. But there may well be a nobler and stronger reconstruction, with friendship and understanding, instead of dominion and subservience, as its solvents. The connexion of Britain and India stretches over more than three centuries, and provides the common ground on which East and West can come into a civilized relationship.

‘John Keats’, said his brother George, ‘was no more like “Johnny Keats” than he “was like the Holy Ghost”.’ When Tagore’s first English book appeared, and was seen to be mystical and religious, expectation was pleased. ‘Oriental literature’ was known to be like that; the West had made up its mind about ‘the East’, and a few stereo-typed generalizations were applied to cover the most diverse facts. Tagore, however, was not in the least like what he was supposed to be. He wrote, with a skill and virtuosity hardly ever equalled, in a tongue which is among the half-dozen most expressive and beautiful languages in the world, and the circumstances of his life afforded him leisure and opportunity, as well as ability, to observe the world outside India. I hope that my reader will see that his work was varied and vigorous and had more than a soft wistful charm, deadened by repetition; and that his spirit was brave and independent.

Finally, I have a debt to three persons: to Prasanta Mahalanobis, F.R.S., the final authority on all Tagore’s work—his help, in letters and discussions, was generous beyond my power to express; to Noel Carrington, who examined in detail my book’s earliest draft, to its great gain; and to my wife.

E.T.

Oriel College Oxford

3 March 1946

Publisher’s Note

Edward Thompson died on 28 April 1946 and was unable to read the proofs.

Book!

1861-1886

Early Life and Poetry

1

Proglegomena

The earliest Bengali literature takes us into a different world from the Hindu one of today. ‘The Brahmanic influence was for centuries at a very low ebb’,1 and Buddhism reigned. Though long since replaced by Hinduism, Buddhism has clung tenaciously to the mind of the people and its influence still works, out of sight yet hardly out of sight. Fragments from an extensive literature which was Buddhist and magical and popular in character survive, some of them recovered from Nepal by Pandit Haraprasad Sastri; these are tentatively ascribed to the tenth or eleventh century. Almost as ancient are hymns discovered by Dr Dineshchandra Sen, which in language of the quaintest simplicity tell the adventures of their hero, the Sun-God, and express a wonder less imaginative but as real as that of the Dawn hymns of the Rigveda:

The Sun rises—how wonderfully coloured!

The Sun rises—the colour of fire!

The Sun rises—how wonderfully coloured!

The Sun rises—the colour of blood!

The Sun rises—how wonderfully coloured!

The Sun rises—the colour of betel-juice!

We are taken a stage beyond these ‘pious ejaculations’ by rhymed aphorisms ascribed to Dāk and Khanā, personages probably as historical as King Cole. These are the delight of the Bengali peasant today; and they ‘are accepted as a guide by millions. The books serve as infallible agricultural manuals’.2

If rain falls at the end of Spring,

Blessed land! Blessed king!

Spring goes;

The heat grows.

Khanā says: Sow paddy seeds

In sun; but betel shelter needs.

About 1200 A.D., the political control of Bengal passed out of the hands of the Sen dynasty. A well-known picture by Surendranath Ganguli3 shows Lakshman Sen, the last independent king of Nadiya, descending the ghāt to his boat with the painful steps of decrepit age, as he fled before the Musalman invaders. With him went into exile, till another handful of invaders gradually brought it back, the nationality of Bengal. Seven hundred years of foreign rule began, and Bengali thought and literature suffered not only because the newcomers were alien in race and religion but still more because of the disintegration resulting from faction and warring courts and the existence of little semi-independent states such as Vishnupur. Bengal was far from the centre of Musalman rule, and about 1340 its government became practically independent of Delhi, and continued so till 1576, when Akbar reconquered the province. During these two hundred years it was cut off from the life of the rest of India, and the people suffered from local oppressors whom its Musalman rulers were unable to control. The seventeenth century was a time of comparative prosperity; but the eighteenth was the period of the decay of the Mogul Empire and the Maratha raids. Till the British rule was established, there was rarely any strong unifying Power, but a series of exacting disintegrating, tyrannies, driving the people’s life into corners and crannies. With no great pulse of national feeling throbbing and making, the land proudly conscious that it was one, the village remained the unit.

Life was narrowed in other ways than political; with the triumph of Hinduism over Buddhism, a process which was probably completed about the time of the Musalman invasion of 1199, caste hardened and women’s lot became circumscribed and veiled. Few countries produce so many poets and novelists as Bengal does. Yet, while the land and blood quicken imagination, for many centuries the life strangled it. The highest literature cannot live without a rich and varied community-life. Bengal produced an abundance of folk-poets; produced, too, court-poets, with gifts of diction and melody. The outward grace, the blossoming of style, was produced. But the tree did not come to fruit, for of a nation, as of an individual, it may be said that it can express itself well but has nothing to express.

Nearly two hundred years after the Musalman conquest of Bengal, Chandidas did for Bengali something of the service which Chaucer, his older contemporary,4 did for English and Dante for Italian—that is, he gave it poetry which vindicated its claims against those of a supposedly more polished tongue. A Brahman priest of a village shrine, he fell in love with a woman of the washerman caste. He used the legend of the love of Krishna and Radha as the cloak of a passion which society regarded as monstrous, and expressed his own ardour and suffering in a great number of songs. This is not the place to discuss their value; but the poet’s genius and his sincerity and depth of feeling set them apart in Bengali Vaishnava literature. He is often particularly happy in his opening lines, which leap out vividly, a picture full of life and feeling. This true lyrist was the fountain of what soon became a muddy monotonous stream, with only occasional gleaming ripples.

As Chaucer was followed by Lydgate, so Chandidas was followed and to some extent imitated by a younger contemporay, Vidyapati, who wrote in Maithili, dialect of Bihar. Vidyapati’s songs have been naturalized in Bengal and more imitated than even Chandidas’s. The Vaishnava tradition was revived a century later by poets who followed in the track of the great religious revival of Chaitanya (early sixteenth century), and there has never been a time when Vaishnava poem have not been produced in every village of Bengal.

Inevitably, out of such an enormous mass of verse some is good, though to the Western reader it seems a never-pausing chatter about flutes and veils and dark-blue garments and jingling anklets.

Musalman rule influenced Bengali literature, by encouraing translation of the Sanskrit epics, which translation the pandits held to be sacrilege. ‘If a person hears the stories of the eighteen Purānas or of the Rāmāyana recited in Bengali, he will be thrown into Hell’, says a Sanskrit couplet. Musalman rule was indirectly responsible, too, for the epic Chandi, written towards the end of the sixteenth century by Mukundaram, a poor man who suffered from Musalman oppression and wrote out of his sense of outrage and helplessness.

In the eighteenth century, the Rajas of Nadiya drew to their court two renowned poets, Bharatchandra Ray, who perfected the elaborate ingenious style, and Ramprasad Sen, the greatest of all Bengali folk-poets, whose sākta songs are often of ineffable charm and pathos.5 But the close of the eighteenth century found poetry exhausted, with nothing to say and no new way of saying it. As the gap between the English Romantic poets and Tennyson and Browning is bridged by Beddoes, so the far wider gap between the vernacular Bengali poets of the eighteenth century and those of the new English influence whom we shall consider presently, is filled by the kaviwallas—‘poet-fellows’—who went from place to place singly or in parties and did the work of the old English miracle-play and the modern music-hall. At their frequent worst, they were scurrilous and obscene; at their best, they continued the tradition of Chandidas and Ramprasad, as Beddoes that of the Elizabethans and Shelley. Their characteristics mark the work of Iswarchandra Gupta and Ramnidhi Gupta also, contemporaries who were not kaviwallas. It should be noted that, up to this date, Bengali literature means poetry, for prose hardly existed.

It was from the West that the new life came. In 1799, William Carey, Baptist missionary, settled at Serampur;6 he found a welcome here, in Danish territory, at a time when missionary effort was excluded from districts under the East India Company’s control. For over forty years he laboured to bring every kind of enlightment, getting invaluable assistance from gifted colleagues. He introduced printing; and from the Serampur literature, chiefly translations and books which imparted information, modern Bengali prose began.

But real literary achievement did not fall to Carey. What foreigners, and pandits working under their direction, could hardly be expected to accomplish was achieved by a Bengali of genius, Rammohan Roy, who was born in 1774. He showed his individuality early; at the age of sixteen he composed an essay against idolatry, which led to ‘a coolness between me and immediate kindred’. He travelled in India, returning home four years after writing this essay. Already a competent scholar in Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic, and learned in Hindu law, religion and literature, he now added English, Greek and Hebrew to his accomplishments, that he might read the Bible, and he made European acquaintances. He opposed idolatry and social abuses, his attacks on widowburning being especially determined; and his attitude ‘raised such a feeling against me that I was at last deserted by every person except two or three Scotch friends, to whom and the nation to which they belong I will always feel grateful’. In 1820 he published The Precepts of Jesus the Guide to Peace and Happiness. He accepted Christ’s pre-existence and super-angelic dignity, but not his divinity. A controversy followed between him Dr Marshman of Serampur; and in 1829, the Unitarian Society of England reprinted his Precepts, with his replies to Dr Marshman, the First and Second and Final Appeals to the Christian Public in Defence of the Precepts of Jesus. He had already gathered a small band of Bengalis, theistically-minded like himself, who held informal meetings, the nucleus of the Brahmo Samaj. In 1830 he visited England, apparently one of the first Hindus to do this. Here he impressed everyone, and made many friendships: and the Select Committee of the House of Commons examined him on Indian affairs. Lord William Bentinck had suppressed suttee the previous year, an action for which Rammohan Roy’s denunciations had prepared the way; and though the latter hesitated as to its expediency he supported Bentinck’s action so effectively in England that the appeal against it was rejected. He died in Bristol on 27th September, 1833; it is pleasant for an Englishman to remember that his last days were surounded by the most devoted care, everything that love could suggest being done to save his life.

It is hard to speak soberly of Rammohan Roy. In the crowded years that followed on his death, his influence was present in every progressive movement, religious, political, social, or literary. His least claim to greatness is that he was the first writer of good Bengali prose. ‘His prose’, said Rabindranath,7 ‘is very lucid, especially when we consider what abstruse subjects he handled. Prose style was not formed, and he had to explain to his readers that the nominative precedes the verb, and so on.’ But in speaking of Rammohan Roy we forget his literary achievement. He stood alone, with the most homogeneous society ever known united against him, he broke the tradition of ages and crossed ‘the black water’. Throughout his search for God he remembered men, feeling for sorrows that were not his and labouring till gigantic evils were ended or at least exposed.

After Rammohan Roy’s death, the Brahmo Samaj was kept alive chiefly by the exertions of Dwarkanath Tagore, the poet’s grandfather. He, too, was one of the first Hindus to visit England, where he was greatly honoured, as ‘Prince Dwarkanath Tagore’. He left a tradition of magnificance, of wealth and prodigal expenditure, and many debts, which his son discharged.

Two streams of movement now flowed vigorously but diversely, yet throwing across connecting arms and from time to time converging: the religious and the literary. Neither can be neglected in our present study, though both can be indicated in outline only. The Hindu College (now the Presidency College, Calcutta) founded in 1816 by Rammohan Roy and David Hare, a watchmaker, in the decades preceding and following the Raja’s8 death was the centre of intellectual life. It found two remarkable teachers, Dr Richardson and Henry Louis Vivian Derozio. The latter was the son of a Portuguese in a good mercantile position, and an Indian mother. His life may be swiftly summed up: born 10th August, 1809, he joined the staff of the Hindu College in November 1826, where he immediately became the master spirit; he was attacked and forced to resign; he started a daily paper, the East Indian; he died of cholera, 23rd December, 1831. Round him gathered a band of students; among whom were found names destined to become distinguished in the next twenty years. They showed an emancipation of mind which often found expression in reckless wildness. They revelled in shocking the prejudices of the orthodox; they would throw beef-bones into Hindu houses and openly buy from the Musalman breadseller, and go round shouting in at the doors of pandits and Brahmans: ‘We have eaten Musalman bread’. A prominent member of the group, who in after years reverted to a rather conservative position, shocked society by the public announcement of his intention to become a Moslem, a farce which he crowned by a mock ceremony of apostasy. These excesses cannot be charged to Derozio’s teaching or example; the new wine was heady and came in over-abundant measure. His attitude was summed up in his noble defence when his enemies compelled his dismissal. ‘Entrusted as I was for some time with the education of youths peculiarly circumstanced; was it for me to have made them pert and ignorant dogmatists by permitting them to know what could be said upon only one side of grave questions? . . . I never teach such absurdity?’ His was a singularly sunny nature. ‘No frown ever darkened his brow, no harsh or rude word ever escaped his lips.’ He taught manliness and virtue, and that his pupils should think for themselves.

Derozio’s school cared nothing for nationalism. On the contrary, everything Indian was despised. The one fact to which they were awake was that at last intellectual freedom had come; compared with this, nothing else mattered. The French Revolution, at a distance of forty years, fired them; European literature inspired and taught them. Unfortunately, with emancipation of mind too often went faults not merely of manners, but of morality, which strengthened the reaction against them. But at first the Derozio group, the intellectual successors of Rammohan Roy, ruled in literature and journalism, showing great activity in social reform.

On the religious side, the stream of Rammohan Roy’s influence ran in other channels. At first the Brahmo Samaj was dormant. In 1845, Dr Alexander Duff, who had founded what became later the Scotish Churches College, the beginnings of missionary educational work, startled Hindu Calcutta by a series of remarkable conversions. His converts were young men eminent not only for family, but, as their after-career showed, for ability and character. One was Lalbihari De, whose Folk Tales of Bengal and Bengal Peasant Life are still read; another was Kalicharan Banerji, for many years Registrar of Calcutta University, one of the founders of the Indian National Congress and a man universally respected. Some of the Derozio group, also, had swung over from their position of extreme secularism, to Christianity. In 1833, Krishnamohan Banerji was baptized, passing over to Christianity from an attitude whose only contact with religion was contempt for orthodox Hinduism. Through a long life he served his country as a Christian minister, revered for his character and his scholarship and his considerable literary gifts. A greater accession still was the greatest poet Bengal had so far produced, known by his Christian name henceforth, Michael Madhusudhan Datta or Dutt.9 Hinduism was alarmed, as Anglican England, a few years, later, was alarmed by the secessions to Rome which followed in Newman’s wake. The tide of conversion was stemmed by Debendranath Tagore, the poet’s father, son of Rammohan Roy’s friend Dwarkanath Tagore. In his Autobiography10 he tells of his alarm and anger.

‘Wait a bit, I am going to put a stop to this.’ So saying, I was up. I immediately set Akshay Kumar Datta’s pen in motion, and a spirited article appeared in the Tatwabodhini Patrikā . . . after that I went about in a carriage every day from morning till evening to all the leading and distinguished men in Calcutta, and entreated them to adopt measures by which Hindu children would no longer have to attend missionary schools. and might be educated in schools of our own . . . They were all fired by my enthusiasm.

In this glimpse of the father some of the famous son’s traits show—his eagerness, his gift for propaganda. Brahmo schools were started, and the Samaj was stirred into activity and reorganized.

The next twenty years were the great years of the Brahmo Samaj. The chief thing to note about these years is the solidarity of Bengali intellectual life. Though the ways and attitude of what I have called the Derozio group repelled Debendranath Tagore, and though his religious enthusiasm, especially his Hinduism, met with little sympathy from them, yet between the two schools there was friendly intercourse. From 1845 onwards the Derozio stream began to flow into the other. Nationalism awoke, and with it swelled the full tide of an enthusiastic intellectual life. During the twenty years following on Duff’s sensational success, Bengal was filled with a pulsing, almost seething eagerness. It was into this ferment that Rabindranath Tagore was born, at the very centre of its activities, on the crest of these energetic years.

Debendranath Tagore firmly established the Brahmo Samaj, and worked untiringly on its behalf. A theist of the most uncompromising sort, he withstood idolatry even in his own family, with ever increasing opposition. In later years he grew more in general sympathy with orthodox Hinduism, withdrew from society and lived much in solitary meditation, receiving from his countrymen the title Maharshi, ‘Great Rishi’11 But, though frequent assertions to the contrary have been made, he never strayed from the Brahmo position as regards such a typically Hindu belief as transmigration. ‘My father never believed in that fairy-tale’, said his son.12 He was staunch also as regards the necessity for social reform.

Debendranath Tagore’s religious conservatism influenced strongly all his sons, Rabindranath not least. Yet it is well to notice how much there was in the Maharshi’s religion which was a new interpretation of Hinduism. His thoroughgoing theism, hating all idolatry and scorning to compromise with it or explain it away, is like nothing before it. Many Hindus, especially poets, have denounced idolatry. But this man gave his life to the firm establishment of a society whose basis is the fervid denial of it. Rabindranath’s theism was of the same clear unequivocal kind.

A few remarks on the relationship between orthodox Hindu society and the Tagores will be in place here. The family are Pirili13 Brahmans; that is, outcastes, as having supposedly eaten with Musalmans in a former day. No strictly orthodox Brahman would either eat or inter-marry with them. Thus, they have no real place in the orthodox Brahman organization. ‘Apart from their great position as zemindars and leaders of culture’, a friend writes, ‘from a strictly social point of view the Tagores would be looked down upon with a certain contempt as pirilis’.

The irony of the situation is their outstanding influence despite this, in everything that matters. The family name is Banerji (Bandopādhyāya). But Thākur (‘Lord’) is a common mode of addressing Brahmans, and was used by the early British officials for any Brahman in their service. Anglicized as Tagore, it was taken over by this great family as their surname.

Though outcastes from orthodox Hinduism, within what we may style the Brahmo Samaj circle, which embraced many who were not members of the Samaj, they stood for all that had affinities with orthodox Hinduism. The family, except for the Maharshi’s immediate circle, was much more orthodox in ceremonial than the advanced Brahmo groups. Readers of the Maharshi’s Autobiography will remember his stand against idolatrous ritual in his own family. In caste also, the Brahmo Tagores,14 though not supporters of it, in practice adhered to it. The friend already quoted suggested to me that the difference is analogous to that between Anglican High and Low. ‘As regards religious principles, there is absolutely no difference between them and ourselves (I write as a member of the Sādhāran15 Brahmo Samaj, while monotheism is even now obnoxious to most of the orthodox Hindus. Adi16 Samaj is High, that is all, while we are Low.’

The Maharshi’s branch of the Tagores followed his lead against all idolatrous practices of any sort; and the poet, going farther, became an uncompromising foe to caste and to division between one Brahmo sect and another.

In 1857 Keshabchandra Sen joined the Brahmo Samaj. His vigour and magnetic powers of persuasion made the Samaj a greater force than ever, the most dominating thing in Bengali thought for the next fifteen years. Yet with his ministry the seeds of schism, which have since brought forth so plentiful a crop, were sown. As is well known, his mind was deeply influenced by Christianity. The more conservative section murmured, and it was only the Maharshi’s affection for his iconoclastic colleague that kept Keshab so long in the parent society. Under the influence of Akshaykumar Datta, their most influential journalist, the other wing of the Samaj was swinging to the extreme limit of Brahmo orthodoxy, where it became scarcely distinguishable from Hinduism. In 1866 Keshab’s party seceded, and became the Bhāratavarshiya17 Brāhmo Samāj,18 later known as The Church of the New Dispensation, the parent body taking the name of Ādi Brāhmo Samāj.

Keshab founded Sulabh-Samāchār,19 the first popular newspaper in Bengali, thereby introducing cheap journalism into his land. Nevertheless, the bent of his mind was neither literary nor political. His direct influence on Rabindranath was not great, but his figure was so important during these formative years that his career cannot altogether be passed over. Without him the poet must have been born into a poorer heritage of thought and emotion. The history of Keshab’s later years is well-known, and does not concern us.

Some of the Derozio group definitely joined the Brahmo Samaj. Others fell under the sway of Positivist thought, which was influential in Bengal. But all remained on friendly terms with the Brahmo leaders. About 1866, the character of the Brahmo Samaj’s impact on Bengali life and thought began to change. At first it did not become less, but it became more general, tingeing the thought of Hindus rather than attracting them to join the Samaj. Today, the Samaj’s actual membership is very small. For many years, however, its three main societies presented perhaps the most notable spectacle the world has seen since medieval times in Italy, of a constellation of ability, in many members brilliant to the point of genius, yet forming an eclectic withdrawn brightness. To the interested Englishman it sometimes seems as if every name which counted in Bengal belonged to these tiny communities. Yet the main life of Bengal, apart from art, swept by, scarcely influenced.

The period 1860-80 was one of expansion and feverish activity. It was the full tide of the Bengali Renaissance, standing in matters literary to the age of Rammohan Roy as our own age of Marlowe and the University Wits stood to the period of Sackville, Wyatt and Surrey. Michael Dutt, in his Tilottama-sambhava, introduced blank verse and the success of his epic, the Meghnādbadbkāvya, established it. It became the accepted medium for serious poetical drama, till prose superseded it. Michael also introduced the sonnet, an alien which made itself at home.

It would be fanciful to find the fact that he was a Christian mirrored in his choice of a hero for his epic, whose hero is not Rama, though the story is taken from the Rāmāyana, but Meghnad, son of Rama’s foe, the demon-king Ravana. But his attitude is summed up in his own terse statement, in which we hear again the frank revolt of the Derozio school: ‘I hate Rama and his rabble. Ravana was a fine chap’. Probably, since Milton was his model, he was remembering Satan, so often alleged to be the hero of Paradise Lost. ‘Though, as a jolly Christian youth, I don’t care a pin’s head for Hinduism, I love the grand mythology of our ancestors.’ It says a great deal for the easy-going tolerance of Bengali opinion that a poet expressing such sentiments, and choosing the pariahs of Hindu mythology as his demigods, should have been taken into the hearts of his countrymen. Bengal has travelled far from the standpoint of the more orthodox South. It has a good deal even of free-thinking, using the word in its restricted vulgar sense, to signify thought which is definitely negative in its religious conclusions.

Michael began with English verse, writing a long romance in the manner of Scott, The Captive Ladie. This is fluent and worthless. But in the Meghnādbadh he was happily inspired to trust his native tongue. Milton was his master and he attained some of Milton’s majesty and splendour of elaborate diction and noble metrical movement. Rabindranath, when aged seventeen, the young Apollo,

though young, intolerably severe’,

cut the Meghnādbadh to pieces. Experience later showed him how much Michael stands out above his contemporaries and successors, and for this criticism he was remorseful. Michael’s diction was a sanskritized one so remote from spoken Bengali as to be difficult for all but good scholars. He used it with the insight of genius and with such feeling for majestic words as Francis Thompson showed, but with none of a philologist’s exactness. ‘He was nothing of a Bengali scholar’, said Rabindranath once, when we were discussing the Meghnādbadh; ‘he just got a dictionary and looked out all the sounding words. He had great power over words. But his style has not been repeated. It isn’t Bengali.’ He keeps an almost unbounded popularity, and there can be very few among Bengal’s thousands of of annual prize-givings where a recitation from his chief poem is not on the programme.

When Michael was the ‘Bengali Milton’—for it was the custom to equate each writer of note with some English name—Nabinchandra Sen, with his aristocratic clear-cut features and haughty air, was ‘the Byron’. His ambitious temperament revealed itself in the subjects he chose. His Raivataka, an epic in twenty books, aimed at throwing round the mythology of Hinduism, already deeply tinged with decay by contact with the modern spirit, the protecting shadow of imagination. He summoned up all the magnificence of ancient legend.

A dim prehistoric vista—a hundred surging peoples and mighty kingdoms, in that dim light, clashing and warring with one another like emblematic dragons and crocodiles and griffins on some Afric shore—a dark polytheistic creed and inhuman polytheistic rites—the astute Brahman priest, fomenting eternal disunion by planting distinctions of caste, of creed, and of political government on the basis of Vedic revelation—the lawless brutality of the tall blonde Aryan towards the primitive, dark-skinned scrub-nosed children of the soil—the Kshatriya’s star, like a huge comet brandished in the political sky, casting a pale glimmer over the land—the wily Brahman priests, jealous of the Kshatriya ascendancy, entering into an unholy compact with the non-Aryan Naga and Dasyu hordes, and adopting into the Hindu Pantheon the Asuric gods of the latter, the trident-bearing Mahadeo, with troops of demons fleeting at his beck, or that frenzied goddess of war, the hideous Kali, with her necklace of skulls—the non-Aryan Nagas and Dasyus crouching in the hilly jungles and dens like the fell beasts of prey, and in the foreground the figure of the half-divine legislator Krishna whom Vishnu, the Lord of the Universe, guides through mysterious visions and phantasms.20

Thus Dr Seal. Yet the same critic adds that, while the ten best books of this colossal attempt deserve to live,

the Raivataka, in twenty books, is a work which can arouse only indignation, we had almost said contempt, for who can read books like the eleventh or the eighteenth without a gnashing of the teeth, or an instinctive curl of the lip?

In the revival of Hinduism, which came as a reaction from Western influence, Nabin Sen was prominent, the poet of the movement. In his Battle of Plassey he sought to arrest disintegration by appeal to patriotic emotion.

Other poets were busy in Rabindranath’s childhood. Hemchandra Baneiji ranks with Nobinchandra Sen: they are the two chief names of this movement, next to Michael. Hem Babu introduced the patriotic note, possibly a greater political service than literary. His Song of India keeps popularity, and is no worse, as poetry, than Rule, Britannia. His epics have reputation, but I am assured that those who praise them most have read them least. His gods and demons are very often and very easily ‘astonished’, and are always ‘roaring’; and their ‘chariots’ ‘run’ through the sky. His vocabulary is very limited; everything is ‘unparalleled’. His description is overdone, and never gets forward; it keeps on turning back upon itself. Rabindranath, when I put this view of Hem’s work before him, agreed with alacrity and asperity, and referred me to Beattie and Akenside for English parallels. Neither Hem nor Nabin ever really touched Rabindranath, and they can therefore be crowded out in a racing survey of the influences that have formed the poet. More important to us is Biharilal Chakravarti, a nearly forgotten poet but a true one. Rabindranath has told21 how Biharilal’s simple music attracted him, when in his teens.

If this chapter aimed at giving a complete survey of all Bengali literary effort, it would contain considerable mention of Akshaykumar Datta’s prose work, long a model of style; and a far more extended notice of that of Iswarchandra Vidyasagar, who took up Bengali prose from the hands of Rommohan Roy. Vidyasagar translated, and wrote didactic and moral treatises, in a sober adequate style. His courage and honesty, his learning and generosity, gave him almost a dictatorship in letters. Then Bankimchandra Chatterji, ‘the Scott of Bengal’, swiftly made his way to the acknowledged headship of Bengali literature. To his popularity let Rabindranath bear witness:22

Then came Bankim’s Bangadarsan,23 taking the Bengali heart by storm. It was bad enough to have to wait till the next monthly number was out, but to be kept waiting further till my elders had done with it was simply intolerable! Now he who will may swallow at a mouthful the whole of Chandrasekhar or Bishabriksha, but the process of longing and anticipating, month af’er month; of spreading over the long intervals the concentrated joy of each short reading, revolving every instalment over and over in the mind while watching and waiting for the next; the combination of satisfaction with unsatisfied craving, of burning curiosity with its appeasement: these long-drawn-out delights of going through the original serial none will ever taste again.

Bangadarsan was a brilliant transplanting of the Western miscellaneous monthly to Indian soil, and by it Bankim showed himself a pioneer in journalism no less than in fiction. Only Sādhanā, the magazine afterwards associated with Rabindranath’s most prolific period, has surpassed it in literary quality and popular appeal. Bankim was a man of genius and abundant versatile force; and had he always written on his best level of truth and achievement, there could be no fear for his fame. Unfortunately, he drifted into the neo-Hindu movement which pressed into service, for the rehabilitation of superstition and folly, grotesque perversions of Western science and philosophy. Popular Hinduism contained no legend too silly, no social practice too degraded, to find support. Any fiction, however wild, was twisted into a ‘proof’ that the discoveries of modern science were known to our ‘forefathers’. If a god careered the skies in a self-moving car, behold the twentieth-century aeroplane and steam-propelled car, both known thousands of years ago, in those wonderful primitive times. Though Bankim was never an extreme neo-Hindu, his name gave the movement an importance it could not have had otherwise, and his work became propaganda. Part of this movement was taken up by Ramkrishna Paramhansa, the ascetic, whom Max Müller has made familiar to Western readers, and by his disciple Vivekananda, whose advocacy gave reaction great vogue. The growing spirit of nationalism kept the tide running strongly.

In no other family than that of the Tagores could all the varied impulses of the time have been felt so strongly and fully. These impulses had come from many men. Rammohan Roy had flung open doors; Derozio and others had thrown windows wide; Keshab came and intellectual and religious horizons were broadened. The tide of reaction had been set flowing by the neo-Hindu school, in battle with whom the poet was to find his strength of polemical prose, his powers of sarcasm and ridicule; and poets and prose-writers had established new forms, and given freedom to old ones. Rabindranath was fortunate in the date of his coming.

2

Early Days

Rabindranath Tagore was born in Calcutta on the 6th of May, 1861. If he was fortunate in the time of his birth, when such a flowering season lay before his native tongue, in his family he had a gift which cannot be over-estimated. He was born a Tagore; that is, he was born into the one family in which he could experience the national life at its very fullest and freest. He was born into that great rambling mansion at Jorasanko, in the heart of Calcutta’s teeming life. The house has grown as the whims or needs of successive Tagores have dictated, rambling and wandering round its court-yards, till it has become a tangle of building. If other houses may be thought of as having a soul of their own, this must have such an over-soul as belongs to the congregated life of ants and bees. If society be desired, it is always at hand; and the Hindu joint-family system, when established on such a scale and with such opulence as here, sets about each member a mimic world, as vigorous as the world without and far closer. Yet for solitude, for the meditation of sage or the ecstatic absorption of child, there are corners and nooks and rooms. In the poet’s Reminiscences, we see a child watching the strange pageant of older folk and their solemn difficult ways. His father, the Maharshi, was usually absent, wandering abroad; the poet, the youngest of seven sons, was left by his mother’s death to the care of servants. Of these servants he has given us a humorous picture, not untouched with malice.

In the history of India the regime of the Slave Dynasty was not a happy one.24

For most of us the sorrows of childhood keep a peculiar bitterness to the end, but the needs of life suppress the memory. Though they were keenly felt, one does not gather that the poet’s sorrows were unusual, in number or quality. His first experiences of school distressed him; but he escaped the ordinary routine of Indian school life, and his education was desultory. One thinks of Wordsworth’s steadfast refusal to do any work other than as the Muse commanded. ‘He wrote his Ode to Duty’, said a friend, ‘and there was an end of that matter.’ Similarly Rabindranath declined to be ‘educated’. Even when his fame was long established, a Calcutta journal demurred to the suggestion that he should be an examiner—in the matriculation, of all examinations—on the ground that he was ‘not a Bengali scholar’.

First, the rambling house in Calcutta, the infinite leisure of days not troubled with much school. Then came gardens and river. An outbreak of infectious fever caused him to be taken outside the city, to a riverside residence. Here came a life fresher, more ecstatic than any before:

Every day there was the ebb and flow of the tide on the Ganges; the various gait of so many different boats; the shifting of the shadows of the trees from west to east; and, over the fringe of shadepatches of the woods on the opposite bank, the gush of golden life-blood through the pierced breast of the evening sky. Some days would be cloudy from early morning; the opposite woods black; black shadows moving over the river. Then with a rush would come the vociferous rain, blotting out the horizon; the dim line of the other bank taking its leave in tears: the river swelling with suppressed heavings; and the moist wind making free with the foliage of the trees overhead.25

He returned to Calcutta, having received the freedom of the fields. Henceforward, as stray lines from the Gita Govinda26 or the Cloud-Messenger27fell on the child’s hearing, imagination could take of the things that had been seen and by them conjure up the Sanskrit poet’s picture. He had begun to write verse himself, and before long his father, who had been watching, as he watched all things, in that silent aloof fashion of his, took him into that wider world beyond Calcutta. He was now to know his native land, a land of very clear and lovely beauty.

There are two Bengals, nowise like each other. There is Bengal of the Ganges, a land of vast slow-moving rivers, great reed-beds and mud-banks, where the population is almost amphibious. Right in the heart of this region is Nadiya, seat of the old Sen kingdom: a place which is Bengal of the Bengalis, legendary, haunted with memories of their vanished independence, sacred as a place where a God or Hero was last shown on earth. Here you find the purest Bengali spoken; it is the place where poets have lived and sung. In after-days, Rabindranath had a home in the very thicket of the reeds and rivers, at Shileida.

The influence of his sojourn here in earliest manhood cannot be over-estimated; it is of the very texture of his poems and short stories. But it was the other Bengal to which he was introduced first. His father brought him for a short stay at Bolpur, the place which is for ever associated with the poet’s fame, because of the school which he established there. This Bengal is a dry uplifted country. The villages are scattered, and there are great spaces of jungle. The landscape of the jungle is of quiet loveliness, such as wins a man slowly yet for ever. At first sight it is disappointing. There are few great trees, and absolutely nothing of the savage luxuriance of a Burmese rattan-chained sky-towering forest or of the ever-climbing dripping might of Himalayan woods; the one good timber tree, the sāl, is polled and cut away by the people for fuel. The mass of the jungle is a shrub, rarely ten feet high, called kurchi; bright green, with milky juice and sweet white flowers. Intermixed with this are thorns; zizyphs28 and pink-blossomed mimosas. The soil is poor and hard. Where there is a tank, you have a tall simul (silk-cotton tree), lifting in spring a scarlet head of trumpet-shaped flowers; or a wild mango. Often the soil cracks into nullas, fringed with crackling zizyph, or crowded with palās trees. These last, and simul, furnish in spring the only masses of wild flowers. Loken Palit29 told me that what he missed, on return from England to India, was our profusion; our hedges crammed with shining beauty, our glades and meadows; after blackthorn, the ponds netted with crowfoot, the water-violets and kingcups and ladysmocks, the riot of gorse and may and wild rose, avenues of chestnut, the undergrowth of stitchworts, the sheets of primroses, violets, anemones, cowslips and bluebells; and, when summer is ending, heaths and heather and ‘bramble-roses pleached deep’.30 Rabindranath himself has spoken to me of this variety in landscape, and also of the beauty of autumn foliage in England. Instead, in Bengal we have only simul and palās. Palās flowers before the leaves come; twisted ungainly trees, holding up walls of leguminous, red flowers, which the Emperor Jahangir thought ‘so beautiful that one cannot take one’s eyes off them’. After these, before the spring quite shrivels in the summer heats, nim and sāl blossom; but their flowers, though exquisitely scented, make no show, being pale green-white and very small.

But the jungle has a peaceful charm which even the great forests cannot surpass. At evening, seek out one of the rare groves of tall trees—possibly preserved as a sacred grove, and with multitudes of crude clay horses round their bases, that the thakur31 may ride abroad—or plunge deep into the whispering wilderness. Wait as the sun sinks, as the leaves awaken. Through the trees you see the evening quietness touching all life. You are not alone, for many scores of eyes are watching you; but of them you catch no glimpse, unless a jackal slinks by or a tiny flock of screaming parrots races overhead. In the distance, the cattle are coming back to the village, the buffaloes are lazily and unwillingly climbing out of the tank. It is ‘cow-dust’,32 the Greek ‘ox-loosing time’.

Or make your way to the open spaces, where only stunted zizyphs grow. Look around on the stretching plain, to the horizon and its quiet lights. Seek out the jungle villages, the primitive life which finds a tank, a mango-grove, and a few rice-fields sufficient for its needs. And you will find the landscape by its very simplicity has taken your heart. In his Banga Lakshmi,33 Rabindranath has personified this attractive land:

In your fields, by your rivers, in your thousand homes set deep in mango-groves, in your pastures whence the sound of milking rises, in shadow of the banyans, in the twelve temples beside Ganges, O ever-gracious Lakshmi, O Bengal my Mother, you go about your endless tasks day and night with smiling face.

In this world of men, you are unaware that your sons are idle. You alone! By the sleeping head you alone, O Mother, my Mother-land, move wakeful, night and day, in your never-ending toil. Dawn by dawn you open flowers for worship. At noon, with your outspread skirt of leaves you ward off the sun. With night your rivers, singing the land to rest, enfold the tired hamlets with their hundred arms. Today, in this autumn noon, taking brief leisure in your sacred labour, you are sitting amid the trembling flowers in this still hour of murmuring doves, a silent joy shining on your lips. Your loving eyes dispense abroad pardon and blessing, with patient, peaceful looks. Gazing at that picture, of self drowned and forgotten in love, gracious, calm, unspeaking, the poet bows his head and tears fill his eyes.

These are idealized pictures, and in them, as in all passionate love of a land, human joys and sorrows have thrown a sanctifying light on the outward face of meadow and forest. But the land itself, where factory and mine have left it unspoiled, justifies its children’s affection.

Rabindranath’s stay at Bolpur was brief. His father, as has been said, was a great wanderer, whose deepest love was the Himalayas. In this, as in so much else, he showed a spirit akin to that of the ancient rishis among whom his countrymen’s veneration placed him. His Autobiography rejoices in the mighty hills, which cast a spell on his soul beyond any other.

Shortly before sunset I reached a peak called Sunghri. How and when the day passed away I knew not. From this high peak I was enchanted with the beauty of two mountain ranges facing each other . . . The sunset, and darkness began gradually to steal across the earth. Still I sat alone on that peak. From afar the twinkling lights here and there upon the hills alone gave evidence of human habitation.34

It is very noticeable how little attraction Nature in some of her grander and vaster manifestations has exercised over Rabindranath. No poet has felt more deeply and constantly lhe fascination of the great spaces of earth and sky, the boundless horizon and white lights of evening, the expanse of moonlight. To the way these have touched him with peace and the power of beauty a thousand passages in his work bear witness. To this aspect of his poetry we are bound to return. But mountains touched his imagination comparatively little. He would not be Rabindranath if he had not laid them under contribution to furnish pictures:

. . . the great forest trees were found clustering closer, and from underneath their shade a little waterfall trickling out, like a little daughter of the hermitage playing at the feet of hoary sages wrapt in meditation.35

But that is not the language of the man on whose soul the great mountains have thrown their shadow, so that he loves them to the end. It has but to be placed beside the authentic utterance, to be seen for what it is, a graceful image which lhe mind has gathered for itself outside itself.

How and when the day passed away I knew not.

The tall cataract

Haunted me like a passion.36

Rabindranath loved Nature, but it was Nature as she comes ‘dose to the habitations of men. His rivers are not left for long without a sail on their surfaces; they flow by meadow and pasture. His flowers and bees are in garden and orchard; his ‘forest’ is at the hamlet’s door. His fellow-men were a necessity to him. Even so, it remains noteworthy how little of mountains we hear in his verse. Of rains and rivers, trees and clouds and moonlight and dawn, very much is spoken; but of mountains little.37

He saw also much of the north-west country, carrying away a particular memory of the Golden Temple of the Sikhs at Amritsar. Already, though only a boy, he had seen far more of his native land than most see in a lifetime.

It was on his return home that he put into effect his magnificent powers of passive resistance, and won the first of many victories. He was sent to the Bengal Academy, and then to St. Xavier’s. But his resolute refusal to be educated stood proof against authority and blandishment and he was allowed to study at home.

3

Juvenilia

The Vaishnava lyrics are the most popular poems of Bengal, with the exception, perhaps, of Ramprasad’s Sākta songs. Their poetical value is over-assessed, a fact which Rabindranath recognized in later years. But they enabled him to find his great lyrical gift, when he read them at the age of fifteen, and gratitude for this great service remained with him, through all his later moods of severity of judgement. In conversation he outlined his two debts to them. ‘I found in the Vaishnava poets lyrical movement; and images startling and new.’ Neither Hemchandra Banerji nor Nabinchandra Sen (he said) produced any new lyrical forms; their metres were experimental and stiff. Thought of them sometimes seemed to make him angry. ‘I have no patience with these folk. They introduced nothing new, their forms were the same old monotonous metre’. But in the Vaishnava poets, language was fluid, verse could sing. ‘I am so grateful that I got to know them when I did. They gave me form. They make many experiments in metre. And then there was the boldness of their imagery. Take this from Anantadas: “Eyes starting like birds about to fly”.’38

The boy-poet read also the story of Chatterton, which exercised its natural fascination; and he made himself a poetical incarnation in a supposed old Vaishnava singer, Bhānu Singh—‘Lion of the Sun’, with a play frequent in his verse, on the meaning of his name Rabi.39 He has told gleefully how these Bhānu Singh songs (first published in Bhārati,40 1877) deceived Vaishnava enthusiasts, and how Nishikanta Chatterji was awarded a German Ph.D. for a treatise on ancient Vaishnava poetry, in which Bhanu Singh was lauded. Rabindranath’s later judgement on the series may be quoted:

Any attempt to test Bhanu Singh’s poetry by its ring would have shown up the base metal. It had none of the ravishing melody of our ancient pipes, but only the tinkle of a modern, foreign barrel-organ.41

The Bhanu Singh lyrics sort and arrange, in as many ways as the poet can think of, the old themes of the Vaishnava singers—the unkindness and neglect of Krishna, the sorrow of deserted Radha, flowers, flutes in the forest, the woman going to tryst in heavy rain. All the time Bhanu Singh chides or consoles or advises the disconsolate Radha. This town-bred boy-poet manages to convey a distinct freshness, as of winds in a wood, and he has beautiful touches. ‘Like dream-lightning on the clouds of sleep, Radha’s laughter glitters’.

His literary career is generally considered to have begun with the Bhānu Singh poems; but much scattered prose and verse had appeared earlier, especially in periodicals. In 1875 and 1876 an essay, World-Charming Intelligence, and two poems, Wild Flowers and Lamentation, appeared in Gyānānkur—Sprouting Intelligence—a magazine. Wild Flowers is a story in six parts. It appeared in book form in 1879,42 in eight cantos, a total of 1,582 lines, not one of which was ever reprinted by the poet.

In 1877, A Poet’s Story, a fragment of 1,185 lines, appeared in Bhārati. This was his first work to be published in book form, a friend printing it in 1878. Its first part is a highly idealized picture of his happy childhood, as the playmate of Nature. Later, become a man (aged fifteen or so!), he thinks by night of poetry, by day of science—this dualism of his thought thus early exhibited. It is fanciful, with plenty of easy personification, nymphs and goddesses:

Night the Poet-Queen would sing

Her magic spells, till everything

One mysteriousness would seem;

All the world a glamorous dream.

Or,

The day the South Wind sighed, the bowers

At her breath burst out in flowers:

That day the bird-quires sang; that day

Spring’s Lakshmi43 went her laughing way.

This is enchanted country, and all young poets have lived in it. But not all young poets have had access to a sublimer realm which this boy-poet knew:

When with clash and shout the storm

Rocked the mountain’s steadfast form,

When dense clouds before the blow

Scudded, frantic, to and fro,

Lone on mountain-peaks I’ve been,

And the mighty ruin seen.

A thousand thunderbolts have sped

With hideous laugter o’er my head;

Beneath my feet huge boulders leapt

And roaring down the valleys swept;

Enormous snowfields left their place,

Tumbled and hurled to the peak’s base.

Better still is this vision of the midnight heavens:

In the wide sky

Didst thou, Primeval Mother, spread

Time’s mighty plumes, far o’er my head,

Those countless worlds there shepherding

Under the shadow of thy wing.

After this, his poetry came out regularly in Bhārati. Rudrachanda, his earliest play, appeared as a book in 1881, and has not been reprinted, except for two songs. It consists of 800 lines, in fourteen scenes. The affectionate dedication to his elder brother Jyotirindranath tells us that it was written before he left for England, when he was sixteen or seventeen. The piece is poor melodrama. Pity, a novel, came out serially, ‘a very indifferent imitation of Bankim, and not even interesting’.44 Then there were stories in blank verse, Gāthā—Garlands or Songs—influenced by Scott’s metrical romances. ‘I do not even remember what they were about’, the poet told me. ‘My sister has a book called Gāthā. I suppose it must be these’. We find many scattered pieces, chiefly lyrical: A Morning-Song, Even-Song, Woman, The First Glimpse, The Love of a Nymph, Lilā45 (an untranslatable word which we shall meet later). These themes are orthodox, and the titles do not excite surprise in those familiar with poetical beginnings. More distinctively Indian are Āgamoni—The Coming (1877, Bhārati), a poem celebrating the coming of the goddess Uma to her father’s home, Salutation to India (1880, Bhārati), and Kāli in Siva’s Heart (1877-1880, Bhārati).

But it is the prose of this period which shows best how alert and eager his mind was. In 1877, he published in Bhārati an essay, The Hope and Despair of Bengalis, in which a master-theme of his whole life appears, the necessity of East and West to each other. Europe’s intellectual freedom and India’s conservatism, Europe’s arts and India’s philosophy, Europe’s independence and India’s mental tranquillity, must be moulded together, this boy insists, ere a better civilization can be made. In the same year, he turns his attention to the connexion between language and character, between literary and moral progress, and says ‘A race cannot improve unless its language does’. In 1878, one number of Bhārati contains articles on The Saxons and Anglo-Saxon Literature, Petrarch and Laura, Dante and His Poetry, and on Goethe, all by Rabindranath. A sufficiently comprehensive sweep of interest, however second-hand and slight the knowledge, for a boy of seventeen! In 1879, Bhārati has articles on The Normans and Anglo-Norman Literature, and on Chatterton.

Before he was eighteen, he had published nearly seven thousand lines of verse, and a great quantity of prose. From my quotations, the readers will have noted how like European, and especially English, poetry his early poems are. His considerable acquaintance with English poetry was great gain. The Sanskrit poets gave him a sound body of traditional Indian art, to keep his own work essentially vernacular. But the English Sarasvati may fairly claim from her Bengali sister a good deal of the credit of his training. Some of this, at any rate, came in England itself, for which he sailed in the autumn of 1877, returning fourteen months later.

About this visit to England he has written, with a humour that is half-bitterness, in his Reminiscences, He went to school at Brighton, where he was kindly treated by the other boys: he saw for the first time the earth white with snow; he left school, and went into dreary lodgings in a London square: he found a pleasanter home with a doctor, and he attended lectures on English literature at University College. I heard him speak of the pleasure which came from reading the Religio Medici with Henry Morley. Also, “I read Coriolanus with him, and greatly enjoyed it. His reading was beautiful. And Antony and Cleopatra, which I liked very much’. A class-fellow was the brilliant and unfortunate Loken Palit, afterwards in the Indian Civil Service. A section of the Reminiscences is devoted to this friendship. Loken Palit lives, with all who ever met him, for his abounding enthusiasm, his keen joyousness. ‘Like an arrow meeting a cross wind’, he himself fell short. But his appreciation and understanding stimulated his friend.

Rabindranath returned to India apparently bringing little from his visit but some memories by no means all pleasant, and a knowledge of some plays of Shakespeare and the Religio Medici.

Letters of a Traveller to Europe appeared in Bhārati (1879-1880), and were re-issued as a book, still in print. They criticize the conduct of English ‘society’ ladies, and express genuine though patronizing admiration of the ladies of what used to be called the middle classes. Rabindranath thought more favourably of the social morality of the West, as compared with that of the East, than his eldest brother Dwijendranath, editor of Bhārati, liked, and the brothers had a sharp controversy in that magazine.

He completed The Broken Heart, a lyrical drama begun in England, a very sentimental piece. It was published, and a hill-potentate sent his chief minister to the author to express his admiration. Today the poem has fallen into a gulf of oblivion, whence Rabindranath has refrained from rescuing, it, except for a few songs and short passages. It is haunted by one of his favourite plots. A poet does not realize that he loves a girl till he has deserted her; he wanders from land to land, and returns to find her dying.

His English stay further manifested its influence in The Genius of Vālmiki, a musical drama. Music was always a main passion with him—he was a fertile a composer of tunes as of songs, and from his brain meaning and melody often sprang together—and while in England he had paid some attention to Western music. The tunes of The Genius of Vālmiki are half Indian, half European, inspired by Moore’s Irish Melodies.

The piece keeps a place in his collected works. It is prefaced by three sentences deprecating any attempt to read it as a poem, apart from its music. It treats crudely, in a multitude of tiny scenes, the Indian legend of the robber-chief who became the author of the Rāmāyana. Valmiki, members of his band, Sarasvati—first disguised as a little girl whom the robber chieftain rescues from his followers, who wish to sacrifice her to Kali; and then apparent in her proper majesty, to reward her saviour with the gift of poetry—and Lakshmi rush in and out of the play, in a fashion which recalls nothing so much as rabbits popping in and out of their burrows on a warm summer evening. There is a chorus of wood-nymphs, who open the play with a lament which recalls Tennyson’s, infelicitous introduction of Titania46 (‘if it be she—but Oh, how fallen! how changed!’ from the imperious empress of A Midsummer Night’s Dream!) from The Foresters.

My soul weeps! It cannot bear it, cannot bear it! Our beloved woods are a burning-ground. The robber-bands have come; and destroy all peace. With terror the whole landscape is trembling. The forest is troubled, the wind weeps, the deer start, the birds sing no longer. The green companies of trees swim in blood, the stones burst asunder at the voices of piteous wailing. Goddess Durga, see! These woods are fear-stricken: Restrain these lawless men, and give us peace!

Despite the accusations of this chorus, the robber-band seem pretty harmless folk. They bluster a good deal, and make a great show of being very violent. But the only person they seem to intend harm against is the disguised Sarasvati, and their chief does not have any real difficulty in checking them here. There is dignity in the long speech with which Sarasvati closes the play:

Listening to thine immortal song, the sun,

Child, on the world’s last day his course shall run.

Long as the sun endure, long as the moon,

Thou to thy harp shalt sound thy mighty tune,

O first and chief of poets!

Had Rabindranath died at Chatterton’s age, a Bengali47 Dr Johnson might have used similar words of his abundance. Lowell’s words on Keats recur to memory.

Happy the young poet who has the saving fault of exuberance, if he have also the shaping faculty that sooner or later will amend it!

Prose and verse flowed in equal volume, as they flowed ever after, his vein resembling that waterfall, in whose praise his mind spontaneously found her true freedom, as he has told us.48

Of this early period—his Saisabkāl, as he has styled it, or Childhood—he selected forty-seven poems or parts of poems, under the title of Kaisorāk—‘Juvenilia’, in the first collected edtion of his poems in 1896. These, with the exception of twenty Bhānu Singh songs, are all he cared to preserve. More than eleven thousand lines of verse published before he was twenty he never reprinted. He was sufficiently known as a rising poet, for a selection of his earliest verse to be issued in 1881, as Saisab-Sangit—Songs of Childhood.

The pieces show him in possession of a device which he was to use far more than most poets, that of repetition and the refrain. The metres are easily handled and are musical. The subjects are not as fresh as the young poet perhaps thought them. There are gloomy pieces, full of the disillusionment which is often the bitter experience of poets not three-quarters through their teens: there are love-poems: there are poems which celebrate dawn and evening and cry for rest: there are poems of journeying. Many are on flowers, one of the earliest celebrating that much-praised flower, the Rose:

Rose-Maiden,

Ah, my Rose-Maiden!

Lift your face, lift your face,

And light the blossomy grove!

Why so shy?

Why so shy?

Hiding close your face among your leaves,

Why so shy?

He narrowly escaped a second English visit. When he was about twenty, he sailed for England, to qualify for the Bar. But Sarasvati was watchful, and frustrated this new attempt to ‘educate’ her son. His companion, an older nephew, suffered so much from sea-sickness that he turned back at Madras. The poet, possibly sea-sick also, accompanied him, doubting of the parental reception which awaited him. The Maharshi, perhaps never very enthusiastic as to his future as a pleader, merely said, ‘So you have come back. All right, you may stay.’

4

The Heart-Wilderness

There is a vast forest named the Heart,

Limitless all sides—

Here I lost my way. — Morning Songs

When The Broken Heart was written, Rabindranath was well launched upon those stormy seas which begin a poet’s career, the period of his introspective sorrows; of his journeyings, not home to his habitual self, but to a false self, full of mournings, sensitive and solitary. Keats has said:

The imagination of a boy is healthy, and the mature imagination of a man is healthy; but there is a space of life between, in which the soul is in a ferment, the character undecided, the ambition thick-sighted.49

That ‘space of life between’ is the mood of Evening Songs. This, like each successive book of verse, for the next half-dozen years, represents a big stride forward, in style and mastery of material, from The Broken Heart and The Genius of Vālmiki. But in its lyrics everything draws its hues from the poet’s mind. The atmosphere is sombre to monotony; thought is choked by vague emotion, or shines dimly through the mists of imaginary feeling. Dr Seal writes of their ‘intense egoistic subjectivity, untouched by any of the real interests of life or society’.50

Yet the poems, in the expressive simplicity of their diction, were in advance of anything then being written. The whole book points to his later achivement, and has an importance out of proportion to its merits. He is feeling his way, and has no sureness of touch in metre, no firm control of cadence. But already there is no mistaking the master of language, the magician who can call up cloud after cloud of rich imagery.

The very first piece shows alike the defects of outlook and theme, and the wealth of fancy. Shortly after its publication, the poet was invited to a marriage-feast at Rameshchandra Datta’s house. As he came up, people were garlanding ‘the Scott of Bengal’, Bankim Chatterji. Putting by the tribute, Bankim said ‘You must garland him. Have you not read his Invocation?’ In the manner of the time, he looked about for an English comparison, and added, ‘It is better than Collins’s Ode to Evening’.

Spirit of Evening!

Sitting alone beneath the limitless sky! Taking the world in your lap, shaking out your dishevelled locks, bending above it your face full of love, full of loveliness! Very softly, very softly, ah! what words, are you whispering, what songs are you crooning to yourself, as you look into the world’s face?

Day after day I have heard those words, yet today I do not understand them. Day after day I have heard those songs, yet I have not learnt them. Only heavy sleep weighs down my lids, a load of thought oppresses my soul. Yet . . . deep within my heart . . . deeper, deeper still, in its very core . . . there sounds a voice which answers to your voice. Some world-forsaking exile from I know not what land is singing in unison with you. Spirit of Evening, ’tis as if some neighbour, a dweller in your own land, a brother almost, has lost his way on this alien earth of my soul, where he wanders weeping. Hearing your voice, it is as if he heard the songs of his own land, and suddenly from far away he responds, he opens his heart. All around he looks; as if seeking you he wanders, restless and eager! . . . How many memories of ancient converse, how many lost songs, how many sighs of his spirit . . . O Evening! have lost themselves in this darkness of yours! Their floating hosts fill your darkness, they wander in the calm heart of Eternity, like broken fragments of a shattered world. I sit at your feet, on this river’s brink, and the flock about me circling around me. . . .

Evening Songs bears the mark of its tentative and transitional character on every poem. All is experimental, both thought and metre. Dr Seal speaks of ‘maenad-like visitings’, which fill the twilight of a young poet’s mind with ghostly wings. But the maenads, after all, were creatures of very considerable vigour. The denizens of the world of Evening Songs are hardly ever ghosts. The poet’s tricks are simple, and in a very few pages we know that we are not ignorant of his devices. There is the repeated striking of one note, till the mind is jaded or maddened, as by coppersmith or brainfever-bird in the sweltering heats. Among poets with any claim to greatness only Swinburne has such a vocabulary of repetitions as is Rabindranath’s Silence, soul, heart, song and speech, lonely, dense, deep, the skirts of the sky or the forest, tears, sighs, stars, bride, caresses, love, death—these are the words with which he weaves and reweaves an endless garland of sad-pretty fancies. There are the same images. The weeping traveller of Invocation is to be a nuisance in the poet’s forests for many a day. These faults flaw not Evening Songs alone, but the books of the next half-decade. It is the more curious that his genius should have stagnated in this respect, when in every other way his progress was so rapid. Even when he was world-famous, though he had enlarged his range of illustration, he had not cast away his besetting risk of monotony and had a tendency, when inspiration failed, to fall back on certain lines of thought and language, and the old tropes reappeared, tears, stars, moonlight. From first to last, he is an extremely mannered poet, as well as a most unequal one. And the sorrow of Evening Songs is as unreal as ever filled a young poet’s mind, in love with its own opening beauty. No Muse weeps on so little provocation as the Bengali Muse; and though Rabindranath’s Muse offends less than the general, she is tearful enough. It is a nation that enjoys being thoroughly miserable!

But the essential thing to remember is that this boy was a pioneer. Bengali lyrical verse was in the making. A boy of eighteen was striking out new paths, cutting channels for thought to flow in.

In Evening Songs I first felt my own freedom from bondage of imitation of other poets. Unless you know the history of our lyric, you cannot understand how audacious it was to break the conventions of form and diction. You may call the metres of Evening Songs rhymed vers-libre. I felt great delight, and realized my freedom at once.51

The reader today must admire the extraordinary freedom of the verse—formless freedom too often, but all this looseness is going to be shaken together presently, the metres are to become knit and strong. Further, this was the first genuine romantic movement in Bengali. The book was ‘defiantly lyrical—almost morbidly personal’.52 In Mohitchandra Sen’s edition of the poet’s works in 1903, when poems were grouped by similarity of character and not chronologically, Evening Songs and earlier pieces were put under the heading ‘Heart-Wilderness’. The title was apt.

The book falls into two fairly clearly-marked divisions. The earlier poems are the more valuable, their thinness and unreality being more than redeemed by zest and by genuine, sometimes exquisite, beauty of detail. The second group are more marred by conceits, and show the poet moving about, or rather floundering, in worlds not realized. All the poems suffer from his trick of parallelism, one of the laziest and most constant of his mannerisms. Here the parallelism is between sing and say.

All is gone! there is nothing left to say!

All is gone! there is nothing left to sing!

In the later poems, catalogues of the raggedest kind, often occur whole passages of this sort:

Compassion is the wind of the world,

Compassion is the sun and moon and stars,

Compassion is the dew of the world,

Compassion is the rain of the world.

Like the stream of a mother’s love,

As this Ganges which is flowing,

Gently to creeks and nooks of its banks

Whispering and sighing—

So this pure compassion

Pours on the heart;

Appeasing the world’s thirst,

It sings songs in a compassionate voice.

Compassion is the shadow of the forest,

Compassion is the dawn’s rays.

Compassion is a mother’s eyes,

Compassion is the lover’s mind.53

It may be said once for all that when in my versions of his early poems a word is repeated—as above, where Compassion sings in a compassionate voice—the repetition is there because in the Bengali. Some day a Bengali stylist will forbid the use of a word too close upon its previous use; but the literary conscience is not sensitive on the point as yet.

This was the period when Shelley’s Hymn to Intellectual Beauty was the perfect expression of his mind—when he could feel that poem as if written for him, or by him.54 Since every prominent Bengali writer was equated with some English one, he was ‘the Bengali Shelley’, and that erratic entrancing spirit was the chief foreign influence on his work. In later years, like other poets, he lost this idol. ‘I have long outgrown that enthusiasm’, he once told me. Yet even in later years he recurred fondly to the Hymn to Intellectual Beauty. Its influence crops up continually in his early work, so often that I shall indicate it only once or twice, leaving the reader, as a rule, to notice it for himself. When he wrote Evening Songs, his mind resembled Shelley’s in many things; in his emotional misery, his mythopoeia, his personified abstractions. But these last are bloodless in the extreme, resembling far more the attendants in the death-chamber of Adonais,

Desires and Adorations,

Winged Persuasions and veiled Destinies,

Splendours and Glooms, and glimmering Incarnations

Of hopes and fears, and twilight Phantasies;

And Sorrow, with her family of Sighs,

And Pleasure, blind with tears, led by the gleam

Of her own dying smile instead of eyes,

Came in slow pomp—-the moving pomp might seem

Like pageantry of mist on an autumnal stream—

than the figures of the West Wind ode—the blue Mediterranean, ‘lulled by the coil of his crystalline streams’, or the approaching storm, with its locks uplifted ‘like the hair of a fierce Maenad’.

Yet if we take Evening Songs at their best, how beautiful in their languorous fashion these poems are! One of the finest songs is Evening—prophetic title and theme. Already there is his power of making an atmosphere. The poem has all the shortcomings of Evening Songs, yet it transcends them triumphantly. There is no depth of feeling—feeling has not begun. It is all abstractions; and the poet is obsessed by the image of a mother and child. But out of this tenuous scuff he makes a lullaby. The metres, winding their cunning monotonous coils, suggest the weaving of spells, the verse seeming to wave arms in incantation. The last paragraph contains the first draft of one of the prettiest things in his English Gitānjali:55

Come, Evening, gently, gently, come!

Carrying on your arm your basket of dreams!

Humming your spells,

Weave your garland of dreams!

Crown my head with them!

Caress me with your loving hand!

The river, heavy with sleep, will sing in murmurs

A half-chant woven in sleep;

The cicadas will strike up their monotonous tune.

And the poem ends with the filmy dreamy atmosphere he loves so well.

It is like Indian music; plaintive and simple, on one strain. Harmony is not used, though later he is to use it magnificently. So he sketches a mood of desolation, in which life seems empty. In The Heart’s Monody he rebukes himself for this one song of shadowy sorrow that he sings. It has some lines on a dove (a shadow—dove, of course):

On my heart’s tumbled foundations, in the still noon,

A dove sits sole, singing its sole tune,—

None knows why it sings!

Hearing its grieved plaint, silence grows with weeping faint,

And Echo wails, Alas! alas!

Heart! Then nothing have you learnt, But this one song alone!

Among the thousand musics of the world,

Ever this one moan!None will hearken to your song!

What matter if they do not?

Or, hearing, none will weep!

What matter if they do not?Give over, give over, Soul! So long

I cannot bear to hear it—this same song! this same song!